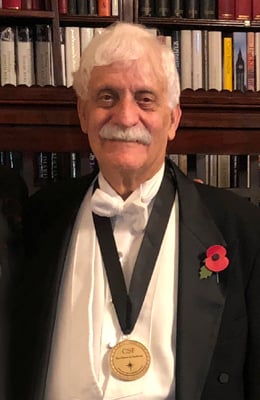

Professor Raymond Damadian, M.D., wearing the Excellence in Medicine medal awarded him by the Chiari & Syringomyelia Foundation at a November, 2018 ceremony in London, England. Photo courtesy of FONAR

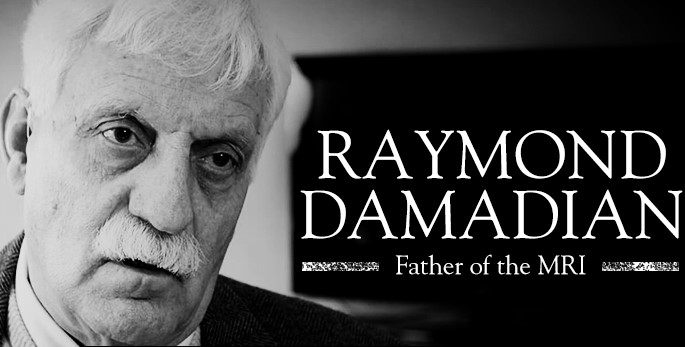

The imaging community has lost a legend, recognized for having revolutionized the field of diagnostic medicine. Raymond Vahan Damadian, MD, “the father of MRI,” died on August 3, 2022, at the age of 86. A true pioneer, committed to medicine and research, Damadian was one of the first to propose the use of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to produce medical images. He was widely recognized throughout his lifetime for his development and commercialization of the world’s first commercial MRI machine, now widely used in clinical applications globally, which has transformed the diagnosis and treatment of disease.

In tribute to his contributions, and to best capture his “indomitable” spirit – also the name of his invention, our editors have compiled a summary of major highlights of his life, work and recognition.

2018: Chiari & Syringomyelia Foundation (CSF) Excellence in Medicine Award

2004: The Franklin Institute Bower Award for Business Leadership

2001: Lemelson-Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Program Lifetime Achievement Award

1998: National Science & Technology Medals Foundation – National Medal of Technology & Innovation in Medicine, presented by President Ronald Reagan

1994: Ellis Island Medal of Honor from the Ellis Island Honors Society

1989: National Inventors Hall of Fame Induction

1978: FONAR was incorporated, introducing the world’s first commercial MRI (a whole-body MRI scanner) in 1980, and went public in 1981.

1977: First MRI body scan conducted on a human, July 3, 1977. It took five hours to produce one image of the patient. After the scan, Damadian and his partner, Dr. Michael Goldsmith, named the machine “Indomitable,” a reference to their struggle to develop the technology.

1971: The journal Science publishes milestone research paper of Damadian’s findings on “Tumor Detection by Nuclear Resonance Imaging”

Milestone Research

In 1971, Damadian’s findings were published in the journal Science. “Tumor Detection by Nuclear Resonance Imaging” (March 19, 1971) documented that cancerous and healthy tissue can be differentiated in laboratory rats using NMR. The Abstract offered the following:

“Spin echo nuclear magnetic resonance measurements may be used as a method for discriminating between malignant tumors and normal tissue. Measurements of spin-lattice (T1) and spin-spin (T2) magnetic relaxation times were made in six normal tissues in the rat (muscle, kidney, stomach, intestine, brain, and liver) and in two malignant solid tumors, Walker sarcoma and Novikoff hepatoma. Relaxation times for the two malignant tumors were distinctly outside the range of values for the normal tissues studied, an indication that the malignant tissues were characterized by an increase in the motional freedom of tissue water molecules. The possibility of using magnetic relaxation methods for rapid discrimination between benign and malignant surgical specimens has also been considered. Spin-lattice relaxation times for two benign fibroadenomas were distinct from those for both malignant tissues and were the same as those of muscle.”

Shortly after, on March 17, 1972, US Patent 3789832 was filed by Damadian. A patent was issued by the US Patent and Trademark Office for “Apparatus and method for detecting cancer in tissue,” on February 5, 1974, according to FONAR, which notes that Damadian held more than 70 patents related to MR scanning.

Indomitable, his original MRI, was given to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

On July 3, 1977, the first MRI body scan was conducted on a human. It took five hours to produce one image of the patient. After the scan, Damadian and his partner, Dr. Michael Goldsmith, named the machine “Indomitable,” a reference to their struggle to develop the technology.

Background

In its feature biography, the National Inventors Hall of Fame acknowledged Damadian’s service and academic work, noting, in part: “Damadian later served as a fellow in nephrology at Washington University School of Medicine and as a fellow in biophysics at Harvard University. He studied physiological chemistry at the School of Aerospace Medicine in San Antonio, Texas. After serving in the Air Force, Damadian joined the faculty of the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in 1967. His training in medicine and physics led him to develop a new theory of the living cell, his Ion Exchanger Resin Theory.”

The depth and breadth of his accomplishments were acknowledged by two presenters who shared their praise of Damadian’s work during an award ceremony in London, England, in November, 2018. The Chiari & Syringomyelia Foundation presented its award to Damadian through Professor Donlin Long, MD, former Chairman of Neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins University, according to a FONAR historical overview.

“As the discovery of penicillin was the most important discovery of medicine in the first half of the 20th Century, Dr. Damadian’s discovery of the MRI was the most important in the second half of the century, and the single most important diagnostic discovery in the history of all of medicine,” said Donlin Long, MD during the 2018 award presentation.

Fraser C. Henderson, Sr., MD, a neurosurgeon, and member of the CSF Steering Committee, added: “Dr. Damadian has revolutionized medicine with his discovery and development of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)…has continued important research using the FONAR UPRIGHT Multi-Position MRI to image and measure cerebrospinal fluid flow…this research may have profound implications for Chiari malformation, Syringomyelia and some of the neurodegenerative disorders.”

CSF noted that as a young child, Damadian watched his grandmother die painfully of breast cancer, acknowledging that this memory fueled his desire to find cures for some of the world’s most devastating diseases. It credited his multidisciplined approach, as a medical doctor and research scientist for his discoveries which were key to opening the door to MRI, noting his membership in the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

Early Life and History of Discovery

Born in 1936 in Forest Hills, NY, Damadian was recognized from an early age as an experimenter. He attended Julliard School of Music, where he studied violin, until he won a Ford Foundation Scholarship, at age 15, to the University of Wisconsin. There, he received a Bachelor of Science in mathematics in 1956, succeeded by a Medical Degree from the Albert Einstein School of Medicine of Yeshiva University in 1960.

A feature article written for the Smithsonian.com, published online in 2000, reported this of Damadian’s initial fore into his pioneering discoveries, noting, “An experimenter at heart, he brought a fresh perspective to NMR — that of a physician”.

Damadian’s first foray into the field of imaging began when, during a postgraduate stint at Harvard University, he experienced excruciating abdominal pains. Doctors detected nothing using x-rays or other conventional methods short of surgery. Damadian decided a better way must be found to examine the inner workings of the body.

The proverbial lightning bolt struck Damadian in 1969, after he used an NMR machine to investigate his ideas about electrically charged particles in the body. His associate Freeman Cope, a Navy physician and physicist, brought him to a small company on the outskirts of Pittsburgh where the two measured potassium, a common electrolyte, in a strain of Dead Sea bacteria.

At breakfast a few mornings later, Damadian wondered aloud about what would happen ‘where you have an antenna wrapped around the human body, where you can look at an atom, and then another atom, and then another atom — you could go from one tissue to the next and, without ever invading the body, get the chemistry of each organ.’ Even Cope thought Damadian’s idea far-fetched, but Damadian committed himself to the quest.”

In 1978, Damadian founded FONAR, for “Field Focused Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” in Melville, NY, making it the first, oldest and most experienced MR manufacturer in the industry. In doing so, the company introduced the first commercial magnetic resonance imaging machine (a whole-body scanner) in 1980, and went public in 1981. Damadian’s MRI was granted FDA approval for the device in 1984.

Award Recognition

Damadian was awarded the Lemelson-Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Program’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2001 for his pioneering work in magnetic resonance scanning technology. In recognition of his work, the Lemelson-MIT award notice noted: “Damadian’s intense curiosity and passion for science led him to develop the first MR (Magnetic Resonance) Scanning Machine – one of the most useful diagnostic tools of our time.”

In 1988, the National Science & Technology Medals Foundation awarded Damadian the National Medal of Technology & Innovation in Medicine, along with Paul C. Lauterbur. The award was presented to the two by then President Ronald Reagan, “For their independent contributions in conceiving and developing the application of magnetic resonance technology to medical uses including whole body scanning and diagnostic imaging.”

The Foundation wrote this tribute of Damadian at the time of his award receipt:

“Astounding achievements are nothing new to Raymond Vahan Damadian. As a teen, he competed against 100,000 other applicants to win a coveted Ford Foundation Scholarship, which he used to earn a degree in mathematics from the University of Wisconsin in 1956. A medical degree from Albert Einstein College of Medicine followed in 1960. But even bigger things would come from Damadian. In 1969, after researching sodium and potassium in living cells, he proposed the first magnetic resonance body scanner. Magnetic resonance had been used to study chemicals, but Damadian thought that it could be used to distinguish tumors from normal body tissue and doggedly pursued his research. Several years later, he built ‘Indomitable,’ the first MR scanner. In 1978, the machine produced the first scans of cancer patients.”

Noteworthy, too, was the absence of one particular award for Damadian. In 2003, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to two of Damadian’s post graduate assistants, who had worked with him when he was a Professor at the Brooklyn, NY-based Downstate Health Sciences University location of the State University of New York’s (SUNY). Paul Lauterbur, an American chemist, and Sir Peter Mansfield, an English physicist, were awarded the Nobel Prize for their discoveries related to MRI. Notably, and quite controversial before and after the selection, Damadian did not receive the prize, although Nobel Prize rules do allow for the award to be shared by up to three recipients. To say controversy preceded and followed the decision would be an understatement.

The Machine and FONAR today

As noted, Indomitable, his original MRI, was given to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. From 1995 to 2008, Damadian’s first MRI machine was on display at the National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) Museum (then in Akron, OH) on loan from the Smithsonian Institution. In 2008, after the museum moved to the campus of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (in Alexandria, VA), it was sent back to the Smithsonian Institution, according to the National Inventors Hall of Fame, in North Canton, OH, according to their staff.