Recovering and Digitizing the desecrated Armenian cemetery of Julfa

By Diana Skaya

In 2013, a small research team from Australia travelled to Armenia in search of traces of one of the oldest Christian cemeteries in the world, Julfa.

Their purpose : to gather photographs and use photogrammetry to construct 3D representations in order to enhance the existing archaeological data, to preserve and reconstruct the abolished cultural site.

Before its final stage of destruction, access to Julfa was restricted.

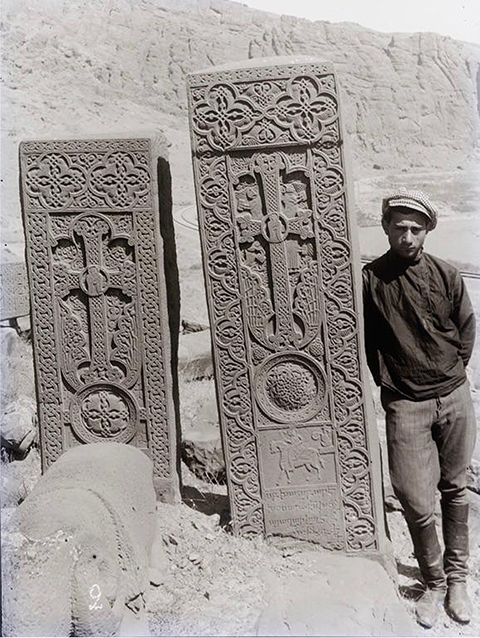

At the beginning of last century, there were 10,000 tombstones in the cemetery, including the most significant collection of khachkars (Armenian cross stones). The cemetery was completely demolished by Azeri troops in 2005-2006, who converted the territory into a military shooting range.

On the 11th of August 2017, Horizon Weekly sat down with co-director of the Julfa Cemetery Digital Repatriation Project in Nakhichevan, Emeritus Professor Harold Short, of the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London, to discuss the Julfa Cemetery Digital Repatriation Project made possible by the Australian Catholic University, among others.

– Professor, you come to the project with digital humanities expertise.

Tell us about the various phases of destruction of the city and of the cemetery. Why and how did that happen?

Julfa was located on the banks of the Arax river between Iran and Nakhichevan, west of the city of Jugha, until its complete destruction, which took place over centuries.

When Shah Abbas forced the population of Julfa to leave, and built the town of new Julfa, many people lost their lives crossing the river. What remained untouched, was the cemetery. For someone of a different culture to recognize the beauty of the khachkars is quite remarkable.

The destruction of Julfa that triggered our interest in the project, was the final destruction at the end of 2005, early 2016 by Azeri soldiers.

During most of the 20th century, Nakhichevan was patrolled by Soviet troops. And although they didn’t encourage visitors to visit the cemetery, they also didn’t completely prevent it.

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the Azeri troops gained control of Nakhichevan, and in 1998 there was an initial destruction phase. With pressure from UNESCO, they laid off. But at the end of 2005-towards 2006, they sent the troops in.

The destruction was filmed by an Armenian priest who was on the other side of the river. It was a cultural genocide, much like the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan by the Talibans in 2001.

– Please talk to us about the Julfa cemetery digital reconstruction project and its purpose.

The primary goal is to construct the most extensive archives related to the Julfa material.

We already have an archive of 2,000 photographs taken systematically in the 1970s and 1980s by an Armenian scholar, Argam Ayvazyan; about 500 photographs taken on glass negatives in the early years of the 20th Century, and nearly 50 tombstones that were removed from the cemetery over the course of the century. All this gathered material provides us with valuable direct evidence.

Secondly, we are aiming to create permanent virtual reality installations in Yerevan and Sydney.

Third, we want to create a touring exhibition that can travel to cities without the resources to establish a permanent installation.

Fourth, to create online virtual reality exhibits and finally, we want to collaborate with other projects and individuals interested in the preservation and reconstruction of destroyed and endangered cultural heritage.

– What is the reason that the project is being based at the Australian Catholic University in Sydney?

Without the Australian Catholic University’s support, the project would not have been possible. With funding from the Gulbenkian foundation and the contributions made by Sydney’s Armenian diaspora, a first field trip to Armenia was organized in 2013.

A small research team was sent to Armenia in order to uncover whether there were sufficient materials and primary sources, (pictures, satellite images, documents, maps) available to create a virtual Julfa 3D cemetery, a digital heritage reconstruction.

The results of the team’s research in Armenia are published in the ebook entitled “Recovering a lost Armenian cemetery”.

The Julfa Cemetery Digital Repatriation Project hopes to restore dignity to the victims that remain buried there and to ensure the public memory of Armenia’s cultural heritage.

For more information about the project visit https://julfaproject.wordpress.com/

”The old photographs are from the set taken by Aram Vrur in the early 20th century. He took the photos on lantern slides, my colleague (co-Director) Judith Crispin was given access to the materials and found that the glass was broken. So she had to put the photographs back together – a bit like a jigsaw – and find a way to hold them together while she took digital photographs. As you’ll see the outcome is amanzingly good, spectacular in some cases. These lantern slides are especially valuable to us in our project because the ‘technology’ of lantern slides means that the detail is very good across the whole area photographed. This means they are usful in our quest to position each khachkar in our virtual reconstruction as accurately as possible in the cemetery – the second of the photos below gives some sense of this.”

Prof. Harold Short