From sojourners to citizens, the Armenian-Canadian experience spans more than a century

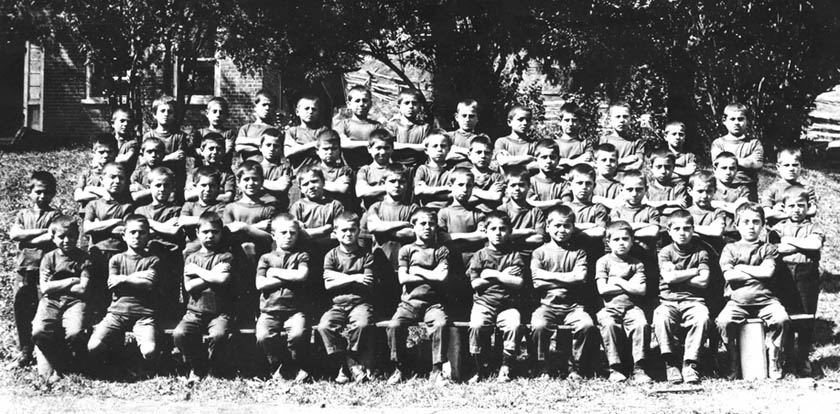

The Armenian Boys’ Farm in Georgetown, Ontario – where more than 100 Armenian children, orphaned during the Genocide, were given a home thanks to the efforts of concerned Canadians Supplied

By Peter Kenter

The National Post

It’s easy to create a list of prominent Canadians with Armenian backgrounds: photographer Yousuf Karsh, filmmaker Atom Egoyan, children’s performer Raffi Cavoukian. But the Armenian-Canadian experience runs deep beneath those celebrated figures, in a story that stretches back to the late 19th century.

“The Armenians who came to Canada in the 1880s and 1890s weren’t really settlers,” says Canadian scholar Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill, author of Like Our Mountains: a History of Armenians in Canada, the definitive study of the subject. “Many migrated to Canada or the U.S. as guest workers and sojourners working to send money home.”

Back then, Armenian workers were directly recruited by the Cockshutt Plow Co. to work in Brantford, Ont. They were also called here from the U.S. as American companies began to establish branch plants in Canada’s industrial heartland. Most, Kaprielian-Churchill says, “had every intention of returning [to their homeland] with enough money to pay off their debts, pay a military exemption tax and invest their capital in farms and other businesses.”

Yet, for many, the outbreak of the First World War shattered any hopes of returning home. And their frustration gave way to horror over news of the Armenian Genocide carried out across the Ottoman Empire beginning in 1915.

“Many survivors returned home following the war to search for their relatives,” says Kaprielian-Churchill. “Those who returned faced a second and third wave of ethnic cleansing.”

By 1924, more than 1.5 million Armenians had been killed, their businesses dismantled, schools closed, churches and monasteries gutted and property confiscated.

“From the early days of the genocide, Canada and Canadians stood with the Armenian community and responded to the calls of the persecuted Armenian population,” says Sevag Belian, executive director of the Armenian National Committee of Canada. “Canada’s response to the Armenian Genocide was one of the first international initiatives taken by the Canadian government to intervene and pressure the international community to act against acts of injustice.”

Kaprielian-Churchill notes that Canadians responded to the crisis with considerable charity, but the government offered no easy path to welcome refugees.

“A lot of money was raised to help Armenians,” she says. “But while it was not easy to come to Canada before 1914, it was more difficult after the war because of the rigorous rules put into place. For example, you had to have a certain amount of money in your pocket, and you had to make a continuous journey to Canada from your country of origin, which was impossible for displaced refugees. They were also afraid that these immigrants would become public charges.”

One exception was the resettlement of more than 100 orphans in Georgetown, Ont., by the Armenian Relief Association of Canada.

The first 50 boys to arrive in Georgetown, Ontario on July 1, 1923. Photograph from the Sara Corning Centre for Genocide Education archives.

Kaprielian-Churchill’s own father came to Canada in 1912, hoping to return to his wife and two children in the province of Erzurum. He searched for his family for years following the war, eventually determining that they had all perished.

“My mother was a ‘picture bride,’ chosen from Armenian women living overseas,” she says. “With the arrival of Armenian women, community and family was established in Canada.”

Kaprielian-Churchill speaks of a happy childhood growing up in Hamilton, where the community was well integrated into the city. Armenian culture was promoted at the local community centre, while children attended Armenian school for three evenings each week.

Today, Armenian-Canadians represent a population of about 100,000, a group Kaprielian-Churchill describes as “another facet of the diamond that makes up the Canadian world.”

But what is that facet’s unique contribution to Canada?

“In my opinion, Armenians in Canada have excelled in two areas: the arts and medicine,” she says. “It’s interesting that these are the same fields Armenians excelled in long ago.”

The community continues to thrive, bonded by a common language, a common culture and the Armenian Apostolic Church, the national church of the Armenian people. However, just as the picture brides who arrived in Canada transformed a group of “men without women” into a community, Kaprielian-Churchill credits the efforts of Armenian women in both sustaining their own community and contributing to Canada at large.

“From carrying on the traditions of needle arts and language, to the efforts of the Armenian Relief Society of Canada and the Armenian General Benevolent Union to support Armenian and Canadian charitable causes, to teachers and mothers, Armenian women have had a prominent role in sustaining their community in Canada,” she says.

Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill is Professor Emerita of History at Cal State Fresno, where she was Professor of Armenian and Immigration History before retiring in 2006. She is currently researching her latest book project, a history of the treatment of children during the Armenian Genocide.

This article was produced by Content Works, Postmedia’s commercial content division, on behalf of The Promise.