Why students in China are learning armenian

- (0)

Motivating students to reach out to all parts of the world fits President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative – the goal is to enrich minds and the economy at the same time

South China Morning Post

In 2012, when He Yang started her college life in Beijing, the then 18-year-old had a clear plan of her future: after graduating from the Beijing Foreign Studies University, known as the cradle of Chinese diplomats, He wanted to work for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Five years passed, her life seems far from that plan. Instead of working as a Russian-speaking diplomat in Beijing, she now studies at a graduate school of Yerevan State University in Armenia, a mountainous nation sandwiched between Turkey and Azerbaijan. Yet still, He is serving a government’s mission.

He is learning Armenian, the language of a country of about 3 million people, less than the population of Berlin. But with Beijing hoping to set a new world order, the demand for talents that can speak languages like Armenian has been skyrocketing. Once considered itself as the centre of the earth surrounded by barbarians, the Middle Kingdom is now actively reaching out, learning the language of countries stretching from Eurasia to Africa.

Such desire is fuelled largely by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s grandest foreign policy, the Belt and Road Initiative, designed to revive the ancient Silk Road trading routes. Since its debut in 2013, Chinese companies have invested at least US$50 billion in member countries. Following the massive Chinese investment is a soaring demand for talents that help facilitate the success of the multibillion-dollar initiative.

The agenda has become so important that it landed on the list of top 100 tasks of China’s 2016-2020 development plan. Backed with government money, in 2016 alone, thousands of Chinese students and scholars headed to countries involved in the initiative for language learning and other studies. At home, Chinese universities which once stuck to only some of the world’s most popular languages, such as French and Spanish, have begun offering language courses that few people in China have ever heard of.

Meri Knyazyan, an Armenian linguist in Beijing, knows this well as she has witnessed how her personal goal – helping the Chinese learn more about Armenia – has been taking a ride on Xi’s ambition of connecting China with the world.

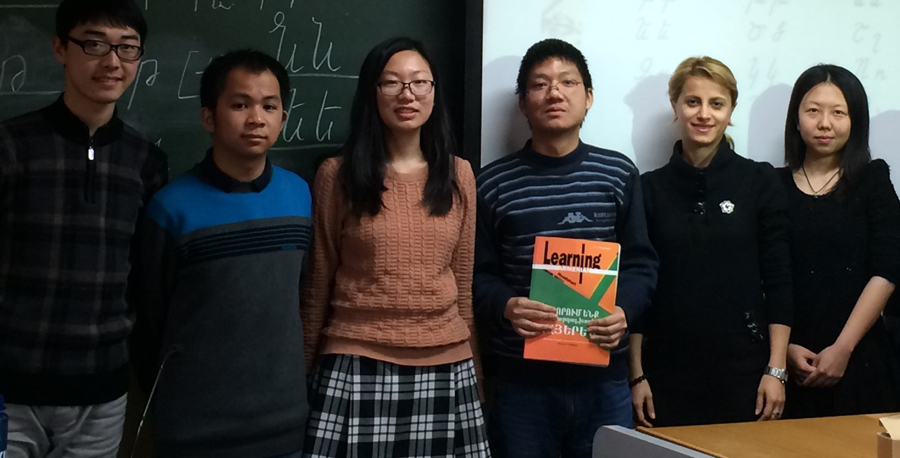

Besides teaching Armenian as an optional course at the Beijing Foreign Studies University, Knyazyan is now helping the university set up an undergraduate programme on Armenian study, the first of its kind in the country. To create more teachers, the university sent two Chinese students to learn the language in Armenia, with a promise that they can land a teaching job after earning a master degree. By contrast, most lecturers at the university hold a PhD degree.

“Language is part of soft power,” Knyazyan spoke of China’s newly found passion in Armenian and other less-known languages. “It is the best tool to understand the culture of local people,” she said.

At Knyazyan’s weekly course, which is open to students from the Beijing Foreign Studies University and elsewhere, the 35 year old organises the screening of Armenian documentary films, introduces Armenian cuisines and tells Chinese students the history of Armenia where early civilisations date back some 6,000 years. Knyazyan said some students became so interested in the country that they travelled to Armenia to see it with their own eyes, bringing back more stories which have lured more Chinese students into the class.

That’s good news for Chinese companies which have been yearning for a greater presence in overseas markets yet often failed to do so, due to a lack of ability in coping with cultural differences. China’s Golden Dragon Precise Copper Tube Group recently suffered from a clash of cultures at its American factory, indicating the struggle of Chinese businesses has persisted even in countries that they have more experience with.

It remains to be seen how the language learning and culture studies will translate into closer relations between China and Armenia, but He, the Chinese student in Yerevan, has already seen some immediate benefits.

“Whenever I speak Armenian, people in Armenia become more friendly,” He said. “I even get better deals at stores by bargaining in the local language.”