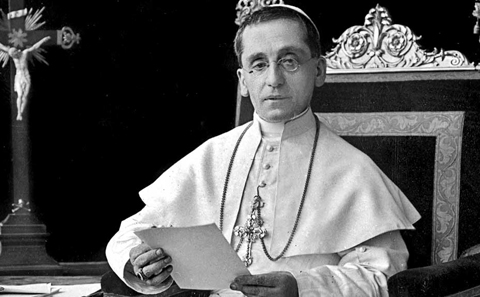

How Pope Benedict XV and Holy See Tried to Stop Armenian Genocide

- (0)

How Pope Benedict XV and Holy See Tried to Stop Armenian Genocide –

German author and researcher Michael Hesemann discusses the Vatican’s efforts to bring an end to the killings of Armenian Christians carried out by the Ottoman Empire.

BY DEBORAH CASTELLANO LUBOV

National Catholic Register

Did Pope Benedict XV and the Holy See try to stop the Armenian Genocide? Well-known German historian Michael Hesemann says the Vatican Secret Archives have provided clear evidence that they did so.

The German author of more than 40 works just had his book, The Armenian Genocide — According to Unpublished Documents from the Vatican Secret Archive on the Greatest Crime of World War I, published by Herbig-Verlag, Munich. He also co-authored My Brother, the Pope with Msgr. George Ratzinger.

Hesemann has spent more than two years locating and studying more than 2,000 pages of never-before published documents on the events of 1915-1916 — the “persecution of the Armenians,” as it was referred to in the Vatican Secret Archives.

In an interview with the Catholic Register in the lead-up to Pope Francis’ June 24-26 visit to Armenia, the German author and researcher discussed the Vatican’s efforts, seeking to save Orthodox believers as well as Catholics, to bring an end to the killings of Armenian Christians carried out by the Ottoman Empire. Their efforts were not successful, unfortunately, and the final toll of Armenians who lost their lives by the time the campaign of genocide ended several years later is estimated at 1.5 million people.

How did the massacres of the Armenian people in Turkey begin? And what was the motive?

There is strong evidence that a violent “solution of the Armenian question” was planned years before the beginning of World War I, actually as early as 1911 at the Youngturk Party Congress in Thessaloniki. They thought: the Turkey of the future had to be a nation of Turks alone, held together by the Sunni Islam as state religion. There was no room in this vision for ethnic and religious minorities.

Did the Vatican and its diplomatic representatives learn of these massacres?

At the beginning of June 1915, Archbishop Angelo Dolci, apostolic delegate in Constantinople, became for the first time aware of the events involving the Ottoman Empire inland areas. “Hundreds of Armenians,” as he still believed at that moment, when he wrote a coded telegram to Rome, “would flee because of persecution perpetrated by Muslims.” When he got further reports on those massacres, in July 1915, he sent a note, asking for mercy for at least the Armenian Catholics, to the grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire. The grand vizier did not provide the slightest response.

You have spoken about the Armenian Catholics. What about the Armenian Orthodox?

Well, the Holy See did not have a direct diplomatic relationship with the Ottoman Empire. It had no nunciature, just an apostolic delegate who originally used the French Embassy, then, after France entered the War, the Austrian Embassy, as his office. So he was in a rather weak position and first felt obliged to help the Catholics.

Also, the Turks used the claim of an alleged Armenian revolt and an alleged collaboration with the enemy, Russia, as a pretext for their persecutions, when indeed, the Orthodox Armenians were only in contact with their Holy Mother See in Etchmiadzin, which was Russian Armenia at that time. The Armenian Catholics spoke Turkish instead of Armenian and were the most loyal subjects of the sultan. Their persecution alone proves that it was not a Turkish countermeasure, but, in fact, an ethnic and religious “cleansing.”

In any case, you can read in the documents that the Secretary of State, Cardinal [Pietro] Gasparri, instructed his apostolic delegate that his task was to help not just Catholics.

Afterward, what did Archbishop Dolci do?

He approached the minister of the interior, Talaat Pasha, together with the Austrian and German ambassadors and the Bulgarian foreign minister at a diplomatic reception. Indeed, Talaat not only promised to end the deportations, but in their presence, also personally cabled the order to Angora (Ankara) to stop the deportation of 7,000 Armenian Catholics. But the very next day, the Turks revoked this order.

What did Pope Benedict XV do when he was informed about the massacres?

When the Pope realized how serious the situation was, on Sept. 10, 1915, he hand-wrote a letter to Sultan Mehmet V, asking for mercy with the Armenians and to stop the deportations and massacres. That hand-written letter should have been delivered directly from the hands of Archbishop Dolci, but the sultan refused to receive the apostolic delegate. It took six weeks, and an intervention by both the Austrians and the Germans, for him to be received on Oct. 23. Another four weeks later, the sultan replied: because “it was impossible to distinguish between the peaceful and the rebellious elements,” he had chosen to deport all Armenians.

What were the effects of the efforts of Pope Benedict XV and the Holy See? Recently published documents have shown that Benedict XV “was the only ruler or religious leader to voice out a protest against the ‘massive crime.’”

Archbishop Dolci wrote on Dec. 12 that “the result was very positive. Not only had it obtained a sudden improvement in conditions, but also the barbaric persecution almost completely ceased.” But towards the end of the year, he realized that at least one million Gregorian Armenians, including 48 bishops and 4,500 priests, were murdered so far and a further half a million had to follow them to the grave in 1916. Furthermore, up to that moment, five Armenian-Catholic bishops, 140 priests, 42 religious and 85,000 faithful became victims of the massacres.

Disappointed, Dolci wrote this letter to Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli, secretary of foreign affairs in the Vatican Secretariat of State, the future Pope Pius XII, admitting that he was deceived by the Turks: “In order to defend Armenian people, I lost the favor of Cesar, the Nero of this unhappy nation,” referring to the Minister of the Interior Talaat Pasha; “he probably realized the strong pressure of the Vatican on the other embassies to stop the massacres. I believe this because from that moment on, he looked at me very badly.”

The killings continued. For Benedict XV, there was no doubt that “the helpless Armenian people went to meet an almost total annihilation,” as he stated in his allocution at the consistory of Dec. 6, 1915. In June 1916, the Armenian Catholic Patriarch informed the Holy See: “it is certain that the Ottoman government has decided to eliminate Christianity from Turkey before the World War comes to an end. And all this happens in the face of the Christian world.”

Did the Vatican and its diplomatic representatives learn of these massacres?

At the beginning of June 1915, Archbishop Angelo Dolci, apostolic delegate in Constantinople, became for the first time aware of the events involving the Ottoman Empire inland areas. “Hundreds of Armenians,” as he still believed at that moment, when he wrote a coded telegram to Rome, “would flee because of persecution perpetrated by Muslims.” When he got further reports on those massacres, in July 1915, he sent a note, asking for mercy for at least the Armenian Catholics, to the grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire. The grand vizier did not provide the slightest response.

You have spoken about the Armenian Catholics. What about the Armenian Orthodox?

Well, the Holy See did not have a direct diplomatic relationship with the Ottoman Empire. It had no nunciature, just an apostolic delegate who originally used the French Embassy, then, after France entered the War, the Austrian Embassy, as his office. So he was in a rather weak position and first felt obliged to help the Catholics.

Also, the Turks used the claim of an alleged Armenian revolt and an alleged collaboration with the enemy, Russia, as a pretext for their persecutions, when indeed, the Orthodox Armenians were only in contact with their Holy Mother See in Etchmiadzin, which was Russian Armenia at that time. The Armenian Catholics spoke Turkish instead of Armenian and were the most loyal subjects of the sultan. Their persecution alone proves that it was not a Turkish countermeasure, but, in fact, an ethnic and religious “cleansing.”

In any case, you can read in the documents that the Secretary of State, Cardinal [Pietro] Gasparri, instructed his apostolic delegate that his task was to help not just Catholics.

Afterward, what did Archbishop Dolci do?

He approached the minister of the interior, Talaat Pasha, together with the Austrian and German ambassadors and the Bulgarian foreign minister at a diplomatic reception. Indeed, Talaat not only promised to end the deportations, but in their presence, also personally cabled the order to Angora (Ankara) to stop the deportation of 7,000 Armenian Catholics. But the very next day, the Turks revoked this order.

What did Pope Benedict XV do when he was informed about the massacres?

When the Pope realized how serious the situation was, on Sept. 10, 1915, he hand-wrote a letter to Sultan Mehmet V, asking for mercy with the Armenians and to stop the deportations and massacres. That hand-written letter should have been delivered directly from the hands of Archbishop Dolci, but the sultan refused to receive the apostolic delegate. It took six weeks, and an intervention by both the Austrians and the Germans, for him to be received on Oct. 23. Another four weeks later, the sultan replied: because “it was impossible to distinguish between the peaceful and the rebellious elements,” he had chosen to deport all Armenians.

What were the effects of the efforts of Pope Benedict XV and the Holy See? Recently published documents have shown that Benedict XV “was the only ruler or religious leader to voice out a protest against the ‘massive crime.’”

Archbishop Dolci wrote on Dec. 12 that “the result was very positive. Not only had it obtained a sudden improvement in conditions, but also the barbaric persecution almost completely ceased.” But towards the end of the year, he realized that at least one million Gregorian Armenians, including 48 bishops and 4,500 priests, were murdered so far and a further half a million had to follow them to the grave in 1916. Furthermore, up to that moment, five Armenian-Catholic bishops, 140 priests, 42 religious and 85,000 faithful became victims of the massacres.

Disappointed, Dolci wrote this letter to Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli, secretary of foreign affairs in the Vatican Secretariat of State, the future Pope Pius XII, admitting that he was deceived by the Turks: “In order to defend Armenian people, I lost the favor of Cesar, the Nero of this unhappy nation,” referring to the Minister of the Interior Talaat Pasha; “he probably realized the strong pressure of the Vatican on the other embassies to stop the massacres. I believe this because from that moment on, he looked at me very badly.”

The killings continued. For Benedict XV, there was no doubt that “the helpless Armenian people went to meet an almost total annihilation,” as he stated in his allocution at the consistory of Dec. 6, 1915. In June 1916, the Armenian Catholic Patriarch informed the Holy See: “it is certain that the Ottoman government has decided to eliminate Christianity from Turkey before the World War comes to an end. And all this happens in the face of the Christian world.”