The Geopolitics of Genocide

- (0)

By Michael B. Oren

Michael B. Oren served as Israel’s ambassador to the United States from 2009 to 2013. Born in the United States and educated at Princeton and Columbia, Dr. Oren has been a visiting professor at Harvard, Yale, and Georgetown, and was a Distinguished Fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem. He earned a PhD in Near Eastern Studies from Princeton. He is the author of the New York Times best-selling Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide, Power, Faith and Fantasy, and Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East.

The phone call from a representative of a mainstream and generally non-political American Jewish organization was sure to be enthusiastic. The year was 2006, shortly after the publication of Power, Faith, and Fantasy, my account of America’s two-hundred year involvement in the Middle East. The book’s revelations included the colonial origins of American Protestant support for late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Zionism. For this reason, the work was welcomed by many of Israel’s American Jewish supporters, among them an anonymous donor who purchased several hundred copies to be distributed to all members of Congress. The gift would be presented by this respected American Jewish organization, its logo stamped on the inside cover. The grant, worth thousands of dollars and redounding to the organization’s prestige, should have been exuberantly received. Or so I thought.

Rather than congratulating me, though, the representative began questioning me about the chapter on American-Middle East relations during World War I. “Are you sure about all your sources?” he asked, insinuating that the hundred-plus pages of footnotes might be insufficient. “You see,” he continued, “we’ve read the part about what you call a genocide. And we have to tell you, on this Armenia thing, we’re kind of with the Turks.”

The organization declined to accept the grant.

As enlightening as its revelations of the deep roots of American Christian Zionism, the book’s unveiling of that “Armenia thing” was shocking. As a historian focused on the modern Middle East—the Arab world, Israel, and Iran—the massacres of Armenians in the Caucuses and Anatolia were, for me, both academically and geographically peripheral. Of course, I knew that the First World War had seen the deaths of a great many Armenians and that an acrid debate still surrounded the definition of that slaughter. Bernard Lewis, my former professor, acknowledged that as many as one and a half million Armenians died in 1915, but denied that the Turkish government deliberately ordered their murder. “On the contrary,” he argued, “there is considerable evidence of attempts to prevent it which were not very successful.” Lewis’s view was refuted by Taner Akçam, a Turkish Muslim, whose books (one of which, A Shameful Act, I reviewed in these pages), documented the senior level decision-making that led to the massacres. “Revenge, revenge, revenge; there is no other word for it,” Akçam quotes Enver Pasa, one of three Turkish ultra-nationalists who ruled Turkey at the time, writing about the Armenians. Another member of that triumvirate, Talat Pasha, specifically ordered “a final end, in a comprehensive and absolute way,” to the Armenian problem.

Still, except for the empathy I felt for the Armenian Americans with whom I grew up in Northern New Jersey, I harbored no strong feelings about whether my neighbors’ grandparents were or were not the victims of genocide. Nor did the scholarly debate especially interest me. Then, I started researching the World War I chapter of my book. Then I entered the archives.

Michael B. Oren

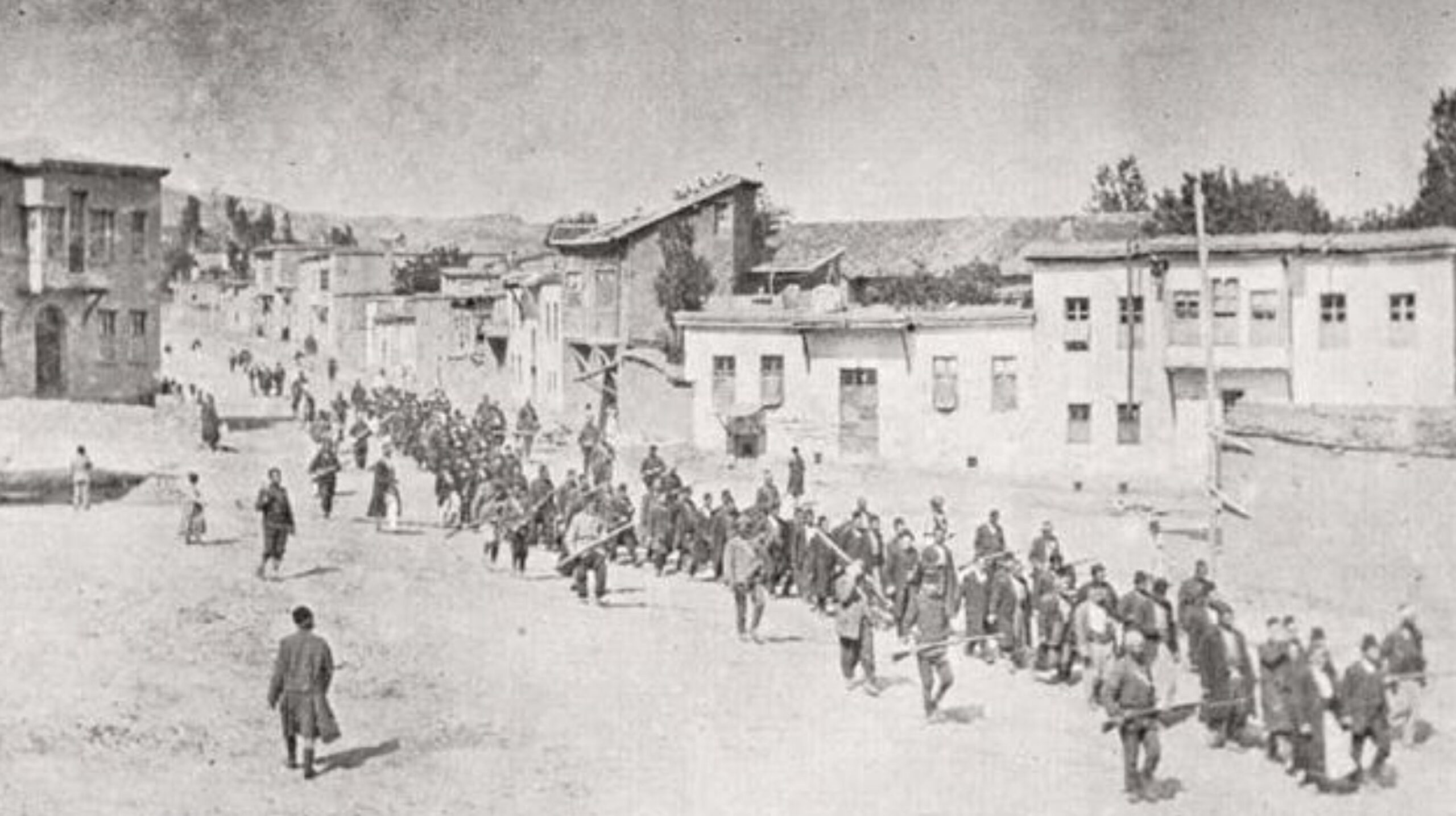

From countless files, the testimonies cried out. Reports from U.S. consul generals in the area, letters from American and British missionaries, and the memoirs of Henry Morgenthau, Washington’s ambassador to Istanbul, and members of his staff—all described in nightmarish detail the systematic execution of hundreds of thousands of Armenian civilians. They were dismembered, crucified, incinerated in their own churches, herded into the Black Sea and drowned, and marched to death in the Syria desert. “Beating and starvation, branding with hot irons, stabbing in the face, burning of hair and beards,” were, according to evangelist Henry Riggs, only some of the tortures inflicted on the Armenians. Witnessing these horrors drove some of the correspondents to near-madness. A deeply depressed Morgenthau resigned. No historian—no human being—could read these agonizing accounts and not be persuaded that Turkey’s leaders in 1915 had embarked on an expressed policy of what Morgenthau termed “race extermination.”

My book, consequently, treated the Armenian genocide as a given and dwelt instead on the individual American reactions—and the lack of their government’s response—to the atrocities. Naively, perhaps, I assumed that the question of whether or not the Turks sought to ethnically cleanse their empire of Armenians had long been resolved. That is, until I received the phone call from the representative of that otherwise uncontroversial American Jewish organization. The academic debate over genocide, I realized, had been supplanted by its geopolitics.

At stake was the West’s relationship with Turkey. Successive Turkish leaders, civilian and military, long regarded the genocide charge as close to an existential threat, the vitiation of everything Turkish. The Ankara government has funded research and even established a museum exhibition to refute the historical record. Yet, what began as a national obsession quickly escalated into a diplomatic and military dispute in 1990, when Armenia declared independence from the Soviet Union. Turkey recognized the republic but, due to border disagreements, never exchanged ambassadors with it. Two years later, another post-Soviet state, Azerbaijan, bitterly warred with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, a 1,700 square mile enclave located inside Azerbaijan but overwhelmingly populated by Armenians. Allying with the Azeris, the Turks closed their border with Armenia. Peace talks, brokered by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, began in 1994 but failed to achieve a resolution. Blockaded to the west and the east, the republic naturally turned north and south—to Russia and Iran. From a question of historical memory, the Armenia genocide was suddenly caught up in a geopolitical maelstrom.

The transformation could be gauged by the changes in U.S. policy toward the genocide. As early as 1975, the House of Representatives recognized the 1915 massacres as a genocide, as did President Reagan in 1981. Since then, though, presidents of both parties have refrained from using the G-word. When, in 2007, the House Committee on Foreign Relations condemned the Ottoman Empire for committing genocide, the Bush White House warned that Turkey might retaliate by cutting off vital air and ground supply routes to U.S. forces in Iraq. Armenia’s ties with America’s Russian and Iranian nemeses did little to fortify its case in Congress.

A more calibrated barometer of the geopolitics of genocide could be found in Israel. Determined to preserve the Hebrew word, Shoah, for the exclusive description of the Holocaust, some Israelis seemed to fear that acknowledging the Armenians’ genocide might detract from that of the Jews. Beyond that unquantifiable concern, though, was Israel’s concrete interests in maintaining relations with Turkey and Azerbaijan. Surrounded by hostile Arab populations, Israelis cherished their friendship with Turkey, especially after 1979 and the loss of their only other Middle Eastern ally, Iran. The rise, starting in 2003, of Turkish prime minister (now president) Recep Tayyid Erdogan reinforced Israel’s reticence on the Armenian issue. Rejected for membership in the European Union, theologically and tactically close to the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas, Turkey under Erdogan turned back to its Middle Eastern roots.

Israeli leaders were already anxious over this drift and were reluctant to accelerate it by revisiting the events of 1915. Israeli President Shimon Peres memorably remarked, “It is a tragedy what the Armenians went through but not a genocide.” At the same time, Israelis began cultivating a robust military and economic relationship with Azerbaijan, a Shi’ite state. Those factors, combined with a desire to stay in lock-step with American policy, militated against Israeli recognition of the genocide.

Paradoxically, as the geopolitical tensions surrounding the Armenian genocide intensified, the academic debate vanished. While some authors differed over whether, like the h in Holocaust, the g in genocide should be capitalized, all concurred on the word. Similarly, scholars understand the need to view the genocide in the contexts of Ottoman and Turkish history, contemporary international and military events, and the dynamics of Armenian identity. Today, virtually no attention is devoted to determining whether or not the murder of 1.5 million people fulfilled the legal definition of “genocide” or the ways in which the world should memorialize their annihilation. If, a decade ago, historians such as Samantha Power, Jay Winter, and Peter Balakian still felt a need to prove the genocidal nature of the 1915 massacres, now, on the hundredth anniversary of those horrors, writers are more seized by the questions of why they took place and what reactions they precipitated.

Those are the focal points of Thomas De Waal’s Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadows of the Genocide. A Carnegie Endowment expert on the Caucasus, De Wall takes readers on an historical, geographical, and personal journey across the genocide’s landscape. In addition to providing a concise survey of the centuries of complex Turkish-Armenian relations, he visits the monuments to the victims and interviews their descendants. History and memory blend effortlessly in his narrative, which emphasizes the progress made toward reconciliation. The Workshop for Armenian/Turkish Scholarship (WATS), founded at the University of Chicago in 2000, for the first time brought scholars from both ethnic backgrounds together to examine the genocide. That healing process was accelerated, De Wall observes, by Hrant Dink, an outspoken Turkish editor and defender of the genocide charge, who was prosecuted and ultimately assassinated for his beliefs in 2007. Dink’s murder, perhaps more than any single occurrence, jarred Turks into confronting their haunted past.

A very different treatment of what Armenians call “the Great Catastrophe” is furnished by Ronald Grigor Suny, a distinguished scholar of Soviet and Caucasus history at the Universities of Michigan and Chicago, the grandson of a well-known Armenian composer. In contrast to its melodramatic title, “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else”—a diktat from Talat Pasha—the book’s subtitle, “A History of the Armenian Genocide,” is an understatement. In fact, Suny has written what is to date the most definitive and probing history. Without in any way justifying the genocide, Suny shows how vast historical forces—the clash between state and empire, Islam and nationalism, East and West—helped forge it. The synthesis of modern European and Middle Eastern studies, political science, international relations, and even psychology galvanizes Suny’s writing. In one paragraph, he asserts:

War and social disintegration, the invasion of the Russians and the British, and the defection of some Armenians to the Russian side [in World War I] moved the leaders of the Ottoman state to embark on the most vicious form of secularization and social engineering, the massive deportation and massacre of hundreds of thousands of their Armenian and Assyrian subjects.

But then counters:

The choice of genocide was not inevitable. Predicated on the long-standing…attitudes that demonized the Armenians…the Young Turks’ sense of their own vulnerability—combined with a resentment at what they took to be the Armenians’’ privileged status, Armenian dominance over Muslims…, and the preference of many Armenians for Christian Russia—fed a fantasy that the Armenians presented an existential threat to Turks…Threat is a perception [that] must be understood not only as an immediate menace but as perception of future peril.

Solid general histories such as Suny’s lay the foundation for more popular and focused works. In Operation Nemesis: The Assassination Plot that Avenged the Armenian Genocide, Eric Bogosian tells the story of Soghomon Tehlirian and other agents of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation who assassinated former Turkish officials. While fighting with the Russian army during the war, Tehlirian lost eighty-five family members to the genocide. The trauma brought him to a Berlin street in 1921 where he shot and killed Talat Pasha, then waited to be arrested. The purpose was to put Tehlirian on trial and provide him with an international stage for telling the Armenians’ story. It worked. After two days of obliging questioning, the young avenger was acquitted and the world informed. Further assassinations—of Djemal Pasha, Behaeddin Shakir, and Said Halim Pasha—reinforced the message that, through legal or illegal means, justice would be wrought.

The grandson of survivors, Begosian draws on his talents as actor, playwright, and director to simultaneously grip and move his readers. The genocide, in his telling, condenses from an abstraction to an intimately painful narrative familiar to readers of Holocaust memoirs. Indeed, Tehlirian’s saga recalls that of the Jewish poet and resistance fighter Abba Kovner, who joined other survivors in a failed attempt to kill millions of Germans after World War II. Tehlirian remains a national Armenian hero. This review was written nearby Kovner Street.

Yet, the personalization and even popularization of the genocide has not impacted its geopolitics. As Laure Marchand and Guillaume Perrier point out in their comprehensive survey, Turkey and the Armenian Ghost—On the Trail of Genocide, the fear of alienating Turkey has blunted France’s attempt to spearhead international recognition of the genocide. Though long enshrined in French law, it has not attained the status of the Holocaust, the denial of which is criminal. Similar caution has characterized the policies of Germany, Russia, and Austria, accused by Erdogan of presenting “claims constructed on Armenian lies.” Most dispiritingly, President Obama who, as a senator, criticized the Bush administration for failing to acknowledge the genocide, has, as president, shown precisely the same reluctance.

Perhaps that refusal will also change. The marking of the hundredth anniversary of the Armenian genocide has spurred a list of new works which, when added to those already published, comprise a formidable corpus. This literature will undoubtedly grow—another far-reaching study, by historians Benny Morris and Dror Zeevi, is due out from Norton soon—and further influence the geopolitical debate. The Armenian genocide may be examined not only as a harbinger of the Holocaust but also, through the mass rape of Armenia women and forced conversion to Islam of thousands of Christian children, of the catastrophes sweeping much of the Middle East today.

In May, Knesset Speaker Yuli Edelstein called on Israel to reexamine its position on the Armenian genocide. “We Jews who are still suffering from the impact of the Holocaust cannot minimize the tragedy,” he said. American Jewish organizations have also changed their position and now join with Armenians in memorializing the genocide of 1915. Their representatives no longer assert, “on this Armenia thing, we’re kind of with the Turks.”