Canadian Armenian Anya Pogharian Creates Potentially Life-Changing Dialysis Machine

- (0)

By Manoug Alemian

A young montrealer of armenian descent might just have come up with an invention that could save countless lives around the world.

Anya Pogharian, 17, submitted a do-it-yourself dialysis machine — which costs $500 to make, vs. the usual $30,000 per machine — as an entry to Google Science Fair 2014.

Dialysis is “a treatment for kidney failure that removes waste and extra fluid from the blood, using a filter,” says the National Kidney Center. It’s used when the kidneys are failing the body, as in the case of diabetes, high blood pressure or glomerulonephritis (chronic inflammation of the kidneys), explains the National Health Service, and can take about four hours per session.

Pogharian, who volunteers at a hospital dialysis unit, saw firsthand how much energy it took for patients to get to their appointments multiple times a week. The machine she created could instead be used at home.

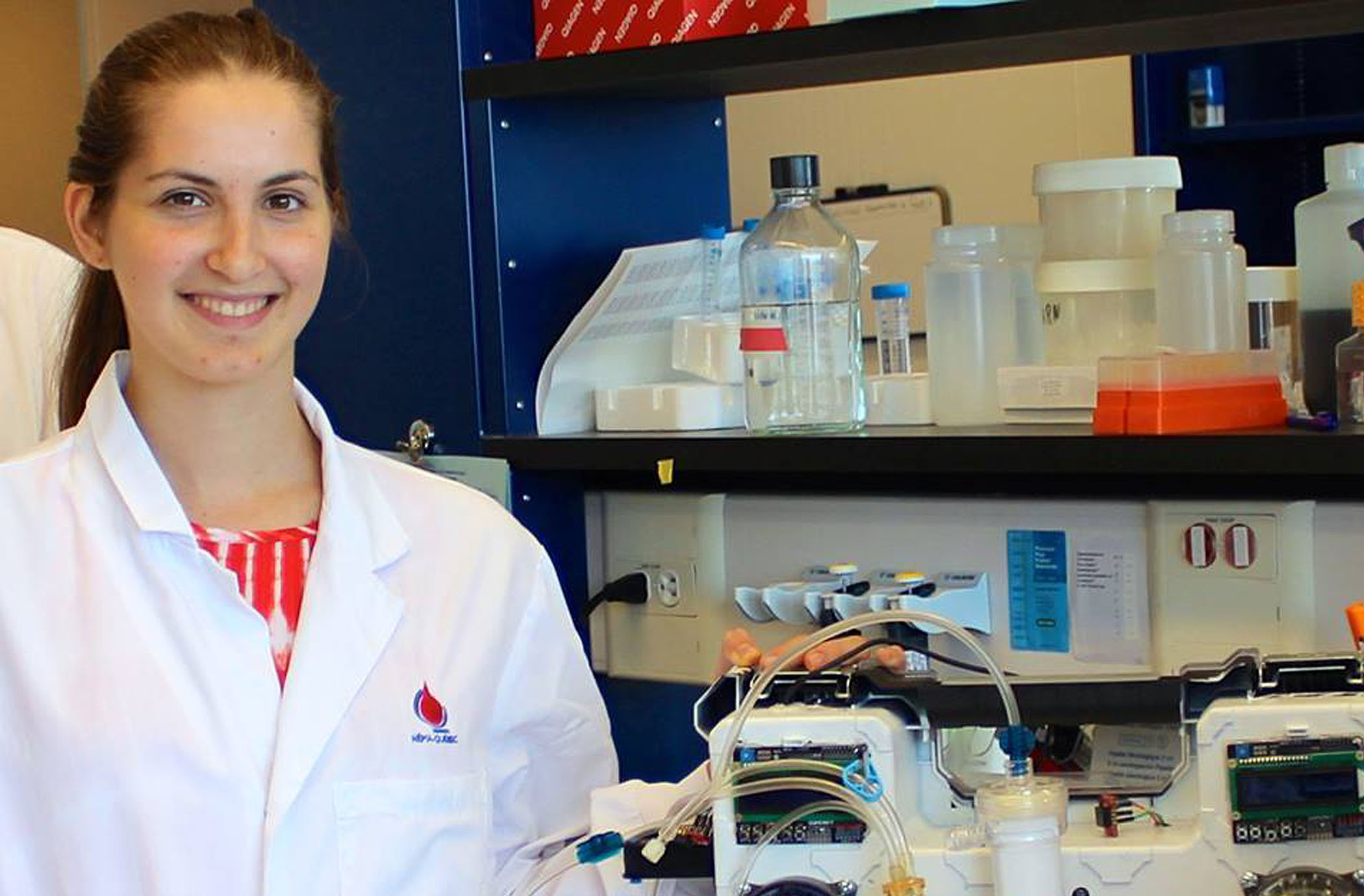

Pogharian developed the machine by reading online manuals of kidney dialysis machines. She’s now received a summer internship from Héma-Québec, an organization that manages the province’s blood supply, among other biological products, and will be able to test out her prototype in a lab.

Horizon Weekly’s Manoug Alemian interviewed Anya Pogharian.

-Everyone on social media saw that this young Armenian teenager invented a machine, but we don’t know anything about you. In a few words, please tell us about yourself?

– I am an 18-year-old college student from Montreal, Quebec who has always been interested in medicine and health. Throughout my high-school years I have been actively participating in a vast range of extracurricular activities. Over the past two summers, I volunteered as a companion to patients with brain injuries at the Montreal General Hospital. While at the General, I also had the chance to train as a volunteer in the dialysis unit. My time spent in that unit inspired me to try to devise a dialysis machine affordable to patients in developing countries. I built a prototype on my own, and my school selected it for entry into the Montreal Regional Expo-Science fair. This lead to the Provincial science fair and finally the Canada Wide Science Fair where I was awarded a bronze medal. Now 2 years later, I am still hard at work on this dream that has become my passion.

– What made you choose that field?

I have always had an interest for health and medicine.. however, my time spent as a volunteer in various hospitals contributed immensely to the further development of my passion.

– Now, most people who read about your invention or quickly glanced through social media: could you explain your invention for our readers in more detail?

After a long research phase, I decided to invest the time and energy in the development of a simple and highly affordable dialysis machine specifically designed for use in the developing world. Bearing in mind that cost is the mainreason keeping the global population suffering from kidney disease, from reaping the benefits of dialysis I made it a personal mission to devise a machine at a fraction of the cost of a typical one which has a price tag of $25,000. This new machine could be shipped worldwide, and built at a fraction of the cost.

During the treatment, blood is pumped by a peristaltic pump through the blood-circuit of the hemodialysis machine to a filter, known as a dialyzer or artificial kidney. Inside the dialyzer, the blood flows through thousands of very fine hollow fibers that are bathed in a dialysate fluid. This fluid is extremely pure and is chemically balanced to have the proper electrolyte concentrations. In another circuit, the dialysate is pumped by a second peristaltic pump to the dialyzer. In the dialyzer, blood and dialysate come together but never mix. Here, toxins in the blood pass through the filter’s semi-permeable membranes by osmosis and move into the dialysate. Finally, the purified blood is reintroduced into the circulatory system of the body and the used dialysate is discarded, just as urine would be discarded. Along the tubing that form the blood and dialysate circuits, there are many pressure, temperature sensors and safety devices to monitor the treatment. This project has two major components: the medical and the engineering. Both have been challenging, but the greatest obstacle has been the coding required for the mechanism to function.

– I imagine this can potentially change the medical industry. What do you think are its possible effects in the future?

– I still have a long way to go to get past the prototype stage, but every good initiative needs a first step. Think about it: my inspiration didn’t spring from past medical projects or feats of engineering.. It came from spending time with dialysis patients. I’m not a doctor or an engineer. I’m a student, like all of you, lucky enough to access the technology and innovation that lets us take on those roles and overcome any obstacle. To date, 30 people from all around the world have approached me personally asking to purchase my dialysis machine either for themselves or for a loved-one. I can only imagine where this project can go, creating a better future for so many around the world.

– What inspired you to create such a machine? Where did the idea come from?

– My personal story of innovation began when I was 16 volunteering at a local hospital a few summers ago as a companion to patients on dialysis, a common way of filtering blood when the kidneys fail. My time spent at the hospital with patients on dialysis is when I began to learn the true potential of innovative thinking.. saving lives. As someone who dreams of becoming a doctor, I naturally became fascinated by this 3 times a week treatment. I began reading up on dialysis, and one thing became immediately clear: There is a worldwide lack of access and a huge need for this treatment. I was in disbelief upon finding out that nearly 90% of patients living in India and Pakistan in need of dialysis do not have access to this lifesaving treatment. Or that from 2002 to 2012 in a region of Nicaragua, 46% of all male deaths were caused by kidney disease. So I thought to myself, “Why isn’t enough being done to help? What if I gave it a shot?”

– How did you feel when you finished your project and when you realized that you invented this new machine that could save money for hospitals and potentially lives?

– It felt amazing to know that I had been able to build a medical device at the age of 17 in my basement all on my own! This was my first science fair project I had no idea how the judges would react. It became clear that all that time spent working on the project was worth it. I learned so much about a variety of different fields.

– After you won your award and then was praised through social media, how did you feel?

Tremendously Encouraged. It felt like all that time spent on the prototypes was worth it. People from all around the world got in touch with me to congratulate me. It’s been an incredible experience for me. I was pleasantly surprised to see only very few negative comments on discussion forums online. It was a huge surprise to wake up one morning and find dozens and dozens of articles in over 8 different languages about the project!

– What was the net effect of this invention? Were you contacted by any hospitals or the government? If so, what was their reaction?

People, organizations, scientific communities appreciate the concept of what I am doing. Creating a dialysis machine that can potentially make accessible a hugely needed treatment to countries with limited ressources. I am aware that although the concept is beautiful the prototype is not yet ready to be used on patients. I still have a long way to go to get past the prototype stage, but every good initiative needs a first step.