Eric Bogosian on Writing ‘Operation Nemesis’ and How the Project ‘Radicalized’ and Changed Him

- (0)

BY ARAM KOUYOUMDJIAN

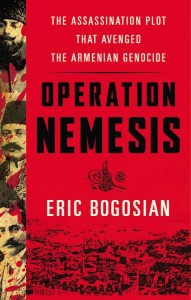

Eric Bogosian’s new book is not a novel or a script or a volume of monologues – the genres for which he is best known. In a surprising departure, Bogosian has written a non-fiction work entitled “Operation Nemesis,” which is about “the assassination plot that avenged the Armenian Genocide,” as its subtitle explains. The book, set for publication on April 21, examines the coordinated Armenian campaign in the early 1920s to assassinate the leading perpetrators of the Genocide in Constantinople (Istanbul), in Tbilisi, and in European cities where they had sought refuge. A significant part of the book is devoted to the assassination of Talat Pasha – one of the Genocide’s key architects – in Berlin by a young Armenian named Soghomon Tehlirian and to the ensuing trial which captured international attention and, stunningly, resulted in Tehlirian’s acquittal.

The multi-hyphenated Bogosian is not an academic or historian; rather, he is a prominent actor, playwright, monologuist, and novelist. Nevertheless, his study of Nemesis is premised on rigorous scholarly research, evidenced by nearly 50 pages of endnotes and bibliographic sources. At the same time, the book is a fast-paced, tension-filled, and altogether accessible work framed in the three-act structure of a script. Part I briefly surveys Armenian history up to and including the Genocide period; Part II tells Tehlirian’s story; and Part III recounts the remaining Nemesis assassinations and ponders their aftermath. Though factually driven, “Operation Nemesis” is layered with analyses of complex geopolitics, including the complicity of Western powers both with the Genocide and the assassination plot that followed.

We can trace Bogosian’s mastery of narrative to his prior body of writing – three novels and such plays as “Talk Radio,” which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and was made into a film by Oliver Stone (starring Bogosian himself), and “subUrbia,” which became a Richard Linklater film. A preeminent monologuist, Bogosian has also penned – and performed – such solo works as “Pounding Nails in the Floor with My Forehead” and “Wake Up and Smell the Coffee.” His acting credits span film (including Atom Egoyan’s “Ararat”), television (“Law & Order: Criminal Intent”), and stage – both Broadway and Off-Broadway.

Ahead of his visit to Los Angeles next week for appearances at the Alex Theatre and at Abril Bookstore, I had the opportunity to speak with Bogosian about his book, the process of its writing, and, ultimately, the impact it had on him. Our conversation of April 18 was lengthy, so the transcript below does not represent its entirety but captures substantial portions of it.

We began our talk with a discussion of identity – and Bogosian’s auspicious birthdate.

ARAM KOUYOUMDJIAN: Were you really born on April 24?

ERIC BOGOSIAN: Yes. Yeah. I didn’t fully understand the significance for much of my life. Oddly, I come from an Armenian family that just didn’t look at things from that perspective. It’s strange, I’m not even sure now why that was, but nobody seemed to be aware of the significance of April 24th in my family.

A.K.: When did you develop that awareness or consciousness of identity, and how did it emerge?

E.B.: I had a very clear idea of who I was as an Armenian from a very young age, because I had a grandfather who had somehow gotten out of Turkey at around the age of 20, so he was prime to be grabbed by the authorities in 1915, and he came to the United States. He used to tell me stories, and he was very clear, basically, that the Turks were bad people and that bad things had happened over there. […]

I had a notion that our being Armenian meant the church because I went to church – I was an altar boy, I went to Sunday school. “Armenian” meant old people who speak another language, “Armenia” meant someplace very far away, seemed to be Middle Eastern, but I wasn’t too sure about that, nobody was ever clear where Armenia was when I was growing up. The food, the music, the weddings – this was all for me my Armenian dimension of myself. Included in that was this narrative of the Genocide, which I understood in the most black-and-white terms. Other than that, I was pretty much part of, you know, regular old knucklehead suburban society and acted like that. I mean, I grew up in the ’60s …

In the ’90s, there was a shift for me, and it came from various directions. One was, very significantly, being in Atom Egoyan’s film “Ararat,” and being on that set where he replicated the city of Van during its siege. He had actors in costume, and it was just one of these odd moments, when I was walking through the set one day, and it just hit me that this must have been what it was like – and it moved me. At the same time, in the ’90s, the strife and the ethnic cleansing that was going on in Serbia and Bosnia was on TV every night, and for some reason it suddenly hit me that what I was seeing was what had happened to my own family. And I also read Peter Balakian’s book “Black Dog of Fate.” All these things started to stir me up, and I was sort of opened to the idea of doing something that would address my Armenian experience.

Having read “Passage to Ararat,” having read “Black Dog of Fate,” I didn’t see the point of me jumping in and telling a similar story talking about the contrast between growing up in the United States around a lot of American things and American TV and so forth, while I have all these very old-fashioned, old-country people around me making shish kabob in the backyard. I cherish those memories, but I felt [this terrain] had been covered by others.

A.K.: How did your interest in the Nemesis story originate?

E.B.: When I heard the story of Soghomon Tehlirian, at first I couldn’t even believe it was true. The notion that a young Armenian had assassinated the leader of the Turks after World War I was news to me. It almost seemed like this had to be some sort of Armenian pipe dream. As I explored it, I found out it was a true story. Certainly, the assassination, the trial, and the acquittal were true stories. I felt this would make a movie. In fact, there had been a movie made about it; at the time I didn’t know that. And so I set about to write this three-act [script].

When I write features or theater, I’m a structuralist as they say, and so I needed to know what the acts were. The first act would be in the desert during the deportation, and Tehlirian seeing his entire family murdered, and [himself] surviving and escaping, which was the story he told in court. The second act would be his running across Talat five years later in Berlin, and shooting him. And the third act would be the trial. It just all made sense. I sat down to do that – that was seven years ago.

As soon as I started researching the story further, I immediately learned about Operation Nemesis. And it was like, What? I mean, Tehlirian was in fact not a student but a member of a clandestine assassination squad operating out of the United States, and this squad had managed to knock off six major Turks after the war. Not only was I amazed by this story, but as I worked on it up until the very end, I continued to be amazed by what these men had pulled off.

When I looked at my particular situation at that time, seven years ago, two things occurred to me. One, if I write this book, it’ll get some attention just because I’m published already, and people know my name, but also, I wasn’t sure whether there was some sort of danger in working on something like this, danger to myself, danger to my children, danger to my career, or even my means of making a living. I thought, well, if there’s a matter of personal threat here, I can handle that, as long as I don’t have to worry about my kids. Well, my kids are in their 20s now, and they can take care of themselves, and my career has sort of peaked many years ago in terms of Hollywood, so that wasn’t going to be threatened either. I thought, you know, you’re in a unique situation to write this book and get it out there.

I wasn’t really thinking about the Centennial at the time because it was years ago, but I felt, you know, not only can you tell this incredible story, which everyone should know about, but also have an opportunity to talk about the Armenian Genocide again. I went on and researched all of this, and for me it was all news. I mean, so many aspects of the Armenian Genocide, as well as the story of Operation Nemesis, were things that I just didn’t know anything about. I didn’t know anything about Armenian history, I didn’t know anything about Turkish history, I didn’t know much about the geopolitics of the region, and I didn’t know any World War I history. So all these things I learned, and I learned very much, of course, about the Armenian political scene in the Ottoman Empire leading up to the Genocide and since then, specifically, the Tashnag [Party] or the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, who were – they were basically the sponsors of Operation Nemesis, they were the parent op organization.

A.K.: You had to tackle this project as a writer and a theater artist, rather than as a historian. In terms of perspective and preparation, was that an asset for you or a liability?

E.B.: I think every field has sort of a built-in tendency for the people in that field to become jaded to the field. You know, after you’ve been around a lot of movie sets or TV sets, the excitement isn’t really there anymore, it’s a job, it’s what you do for a living. Because I had never done anything like this, it was exciting for me all the way through.

I ended up at the University of Michigan with the Armenian Studies Program there, and I worked with those scholars . . . [Also,] fortunately for me, I had become friends with Aram Arkun many years ago, when he was at UCLA, and Aram is one of the most established historians in this field, and he gave me great assistance in learning, because I had to learn at a very accelerated rate . . . Then it turned out that I had other people I had gone to school with who were top translators in their field. I had befriended a French-Armenian filmmaker named Eddy Vicken, who was living in Paris, and he introduced me to [the historian] Raymond Kevorkian, so piece by piece, all the pieces came and fell into place. I actually taught myself how to access archives, which is a lot easier now than it used to be. I have friends in different countries, so I would get in touch with somebody, let’s say in London, and I’d say, can you find me a graduate student who can go into the British Archives and look for this, this, and this on these dates, or somebody in Rome, and so forth. And in a kind of a way, I don’t know, awkward, clumsy way, I put it all together. What was going in my favor was that I had the time to do it, and I was going to keep doing it until it was done. […]

I was just talking with one of the historians last night from the University of Michigan, and she said that when she read the book what was refreshing for her was that I wasn’t just making an argument and then proving it, which is the way [of] most historians. This is more a representation of my own curious mind in saying I’m basically going to get everything in the book that I think you’re going to want to know about.

A.K.: When you were deciding on a genre and opted for a research-based non-fiction book, did you consider the reach it would have – as opposed to the reach a screenplay would have?

E.B.: […] The reason that I felt I had to do it this way was because the subject matter was just too complex, and I know that movies simplify and distort history, so I just thought it was too important to get it right at least once. […] I actually hope that this book will inspire perhaps a really serious scholar – somebody who wants to put 20 or 30 years into it – to really look at what was going on with Operation Nemesis because there are still more archives to get into, and the connections to British intelligence, which I was only able to touch on with my research, are just too fascinating, and I explain why in the book.

I mean, there are characters here in the background who really need to be looked at more carefully because they were obviously playing some very complicated games. Often in history Armenians get stuck between players who have other agendas, not necessarily the agendas that the Armenians are looking for, so in the case of the assassination of these Turkish leaders, the Armenians are avenging the Genocide, but there are other people around at this time who have other agendas that maybe are promoted by removing these leaders and replacing them with other leaders, and in fact, inadvertently that’s what the Armenians did by knocking out Talat Pasha and Jemal Pasha (and also Enver Pasha being killed [by Russian forces] around the same time). This is how Kemal Ataturk was able to take over the country with nothing stopping him – I mean, these were all guys who would’ve vied with him for the leadership of Turkey. And the way Ataturk went about things – I don’t know if people knew that to be the case at the time – but he was a real pragmatist. The history we live with today is that Turkey became a strong ally of the West, and that was established early on. […]

A.K.: Are there any lingering issues that you did not have an opportunity to research, or are there any areas of inquiry in which scholarship is still lacking?

E.B.: We went pretty far into the British side of things, but the modern British intelligence system was always grounded in a lot of secrecy. And it’s very hard to get at what’s really going on in certain circumstances. I explain it very clearly in the book – the dynamics of Aubrey Herbert and others who were involved with this assassination, which I clearly believe they had something to do with it. The archives that I didn’t touch were Russian archives. I think there’s stuff in Russia. Lately, there’s been a lot of talk about Vatican archives just as far as the Armenian Genocide goes, but the Russian archives would be amazing things to get into, and there are archives in the United States that need to be opened, particularly the Tashnag archives in Massachusetts. […]

A.K.: As I read the book, your three-act structure was readily apparent, but I kept debating as to whether the book had a central character – and whether that was Tehlirian, the Nemesis campaign, or the Genocide itself, which you refer to at one point as “the core of what this book is really about.” Is there a central character in the book?

E.B.: The structure of this book went back and forth many times in the time that I wrote it. I had a lot of information I wanted to get out there, and how was I going to do that. I mean, you could imagine different ways this book could work. There was one time when I started with the trial. There were other times when I started with the killing of Talat.

The notion I always had was that there would be this spine which would be the story of Nemesis and how they were put together and how they did what they did, and then any time I got to a certain point, let’s say I mentioned Armenian Christianity, I would take a detour for a while and I would talk about why the Armenians are Christians and how that all began, so that the reader could keep being informed. When I finally came down to the final edit with my editor David Sobel, we found that this structure was very confusing for the reader because I was skipping back and forth in time, and the reader couldn’t understand where we were. Are we in 401 A.D., or are we in 1921, or where are we? So David insisted, Let’s just straighten out this very kinky string, and make everything that happens happen in line temporally. And that ended up solving the book.

Ultimately, the book, as a piece of writing, is kind of Byzantine. It’s the way that I write, it’s the way that I think, and the trick was to try to keep the reader interested, which I think I pulled off, while worming around all these different nooks and crannies that I just thought were too good to not talk about. I mean, the whole part about oil and Calouste Gulbenkian – I just thought this is important, I have to tell the story. The story of what’s a sultan, what are harems, what are janissaries, I just felt, how can you talk about Turks and not really know [who] a Turk is, I have to get this in there. […]

To get back to your question about is there a protagonist, I don’t think there is. I do follow Tehlirian for a long period of the book, because we know more about him than anybody else, there’s more information, and the story of the trial, being told here in a different way, is fascinating in and of itself. So, no, there really isn’t.

A.K.: As an Armenian-American writing this book, you are critical of Western atrocities throughout history, whether they be in the form of colonialism in Africa or the eradication of native populations in the Americas. How do you characterize the refusal of U.S. administrations to use the word “genocide”? When does silence become denial – or turn into aiding and abetting?

E.B.: […] I have been radicalized while I’ve been working on this project. I have shifted just recently from looking at the American government position as – I think I would have characterized it a year or so ago as pragmatic, understandable because Turkey is so strategic and the people who run the government are politicians, and I sort of felt, well, they didn’t have a choice, this is what they have to do. But I don’t believe that today. I think it’s cowardice, and I think it’s absurd because the United States is just too powerful to do things this way. This is the way bureaucracies act, they act weakly because they are run by cowards, and they don’t understand that the best way to deal with a bully is to punch him in the face. It’s absurd because Turkey can’t exist without us. Turkey needs the endless amount of aid that we give them and the support we give them. It is not a viable nation without support from the West. […]

As Robert Fisk was saying yesterday when we were talking about it, it’s ridiculous, it’s just ridiculous. They just have to – say what you need to say: It’s a genocide. And by not saying it, by perpetuating the denial, this is the last stage of genocide … Otherwise, we become complicit, we do become complicit, I agree with that.

A.K.: You mentioned that you’ve become radicalized, so aside from the obvious fact that writing this book has endowed you with a tremendous amount of historical and geopolitical knowledge, how has it changed you?

E.B.: Well, anybody who does the type of research that I’ve done will quickly realize how malleable history is, and once you realize how plastic history is, then all of reality starts to become suspect. […] I think the way I’ve changed is that I was always very certain that I knew things because I read a lot, and I thought I understood history or I understood political situations. Today, I’m not so sure about things, and in that way I’ve changed.

For example, when the Pope made a statement last weekend, on the surface of it, it seems that the Pope is a man of great spine and morality, and he just felt that he had to say what he said. Okay, but there’s also a political context for why he’s saying what he’s saying, and that has to do with what’s going on in the Middle East today with ISIS and so forth. So today I don’t just look at the thing as it sits right in front of me but look at the context, why is he saying it, why is he choosing today to say these things.

Likewise, yesterday the New York Times decided to suddenly, out of the blue, put a big piece right on the front page about Turkey and denial. And, you know, for a lot of us who watch the New York Times very carefully, this was surprising because only a few days before, they had kind of buried the Pope’s statement on page 7. It didn’t make the front page of the paper. How come they changed? Well, I think that they changed because there’s a sort of behind-the-scenes push-pull going on. The Pope said what he said, and then Turkey came back and lashed out with some very strong statements bordering on insults about Argentina, about the West, and then people are getting fired and thrown away [Etyen Mahcupyan, chief adviser to Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu was “retired” after referencing the Genocide], and I think the Pope’s moral spine inspired the New York Times to have some spine and say, If we just keep giving in to them all the time, if the Turks are going to get angry if we run this article, then where does this all lead? What is the point of even saying stuff about the [Genocide], if you’re just going to keep bending over every time this sort of position is taken, so I think there was more to it than just an article about Turkey on the front page yesterday.

So that’s how I’ve changed.

Aram Kouyoumdjian is the winner of Elly Awards for both playwriting (“The Farewells”) and directing (“Three Hotels”). His play “Happy Armenians” is slated for production this fall.