Turkey’s Armenian Ghosts

- (0)

Turkey’s Armenian Ghosts

For many years in Turkey, conversations became awkward if they turned to defining what used to be called the “events of 1915”. Basically, I had read one set of history books, which discussed the genocidal deaths of 1-1.5 million Armenians who died in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War deportations. Most Turks had read a completely different set of books. If there was a mention of the Armenian question at all, it was suggested that some unfortunate wartime accidents had been exaggerated by Turkey’s enemies as part of great conspiracy to do the country down.

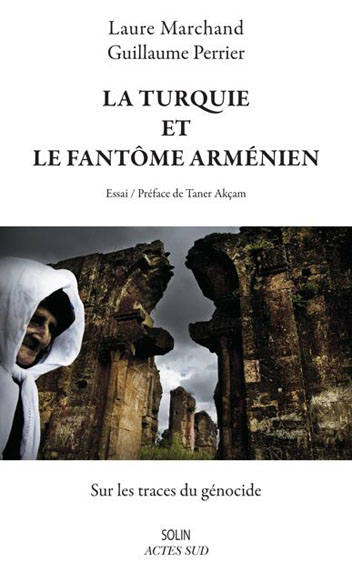

This old lady in Ergen (Dersim/Tunceli, Turkey) is an Armenian who converted to Alevism, the heteredox faith influenced by Islamic Shia thinking that predominates in that province.

Discussion, therefore, would usually soon choke up, having revealed a genuine absence of knowledge of what happened to the Armenians, accompanied by a naturally offended sense of personal innocence; a counter-assertion of the never-addressed trauma of the wrongs done to millions of Muslims expelled from their homes in the Balkans and elsewhere in the 19th and early 20th centuries; legalistic arguments about how by the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide cannot be applied retrospectively; and among a few who worried that something awful could have happened, fears that any recognition of an Armenian “genocide” would result in expensive reparations, awkward atonement, and, not least, odium or worse for contradicting the official narrative of denial.

With such minefields to cross, therefore, I found I alienated less people by discussing basic facts of the case rather than how to label it. I agreed with the advice of Hrant Dink, the late Armenian newspaper editor, who would say it was counterproductive for outsiders to insist upon one formula or another until Turkey was ready to debate fully and reach its own conclusion. He believed that processes like Turkey’s EU accession would bring freer information, and with that, understanding of what really happened. The trouble is, Dink was murdered in 2007, perhaps precisely because he represented what should have been a joint Armenian-Turkish road to reconciliation. Sadly, Turkey has yet to get far in undoing the official ideology of denial and hostility to Armenians that formed the mind of the young nationalist who pulled the trigger – let alone bring to justice acts of official negligence and even official complicity with this killer.

The authors’ inventory of discoveries shows just how much that is Armenian has carried through into modern Turkey. They then use these to make a controversial yet compelling argument: that the Turkish Republic founded in 1923 shares moral responsibility for whatever happened to the Armenians. They contend that Turkey’s many decades of denying that there was anything like an Armenian genocide is actually part of the continuation of a pattern of actions by the Ottoman governments responsible for the Armenian massacres and property confiscations of the 1890-1923 period. For instance, the judicial “farce” of the investigation and trial of Hrant Dink’s murderer is, to the authors, proof positive that “since 1915, impunity has been the rule”.

There are other rude shocks. Some Turks now realize they were being misled by the old official narrative of denial, thanks to a new openness about and better understanding of the Armenian question in Turkey over the past decade. But how many appreciate that Istanbul’s best-loved Ottoman landmarks are often designed by Armenian architects? How many know that the famed Congress of Erzurum, corner stone of the republic’s war of liberation, was held in a just-confiscated Armenian school? And how many have heard, as Marchand and Perrier allege, that even the hilltop farmhouse that became the Turkish republic’s Çankaya presidential palace was seized from an Armenian family – and that descendants of the family, some of whom were well-enough connected to escape with their lives — can calmly be interviewed about this “original sin” of the republic? (The official history of the palace simply says that Ankara municipality “donated” it to republican founder Kemal Atatürk in 1921).

It seems apposite that the authors quote Çankaya’s current incumbent, the open-minded President Abdullah Gül, as saying while he toured the ruins of the ancient Armenian capital of Ani on Turkey’s closed border with Armenia: “That’s Armenia there? So close!”

Amid such evidence that Turkish perceptions can be naïve, one problem with the book is its unrelenting insistence that Turkey end its “fierce” and “obsessive” denial that a genocide happened (unlike, the authors point out, Germany, Serbia, Rwanda and others). This tight argumentation leaves the impression of a Turkey that is deliberately calculating and somehow evil, rather than the more likely case that it is clumsy, embarrassed and a prisoner of its own contradictions. A preface by U.S.-based Turkish academic Taner Akçam, a once-lonely pioneer who calls for Turkish recognition of the Armenian genocide, sets a trenchant tone and outlines the problem. “To recognize the Armenian genocide would be the same as denying our [Turkish] national identity, as we now define it”, Taner writes. “Our institutions result from an invented ‘narrative of reality’… a coalition of silence … that wraps like a warm blanket…if we are forced to confront our own history, we would be obliged to question everything”.

Marchand and Perrier brush aside any need for a transitional commission to study the history of the genocide, as suggested in the still-born 2009 protocols between Turkey and Armenia, because the genocide “is a fact that that is barely debated in scientific circles”. Even though the study of Russian archives on the matter is still in its infancy, for instance, the authors dismiss valid elements of the Turkish narrative as yet more ghosts whose abuse has made them an extension of the earlier misdeeds. Parts of the Turkish story are therefore mentioned in passing or only partially, like the massacres of Turks and Muslims by Armenian militias operating behind Russian lines, the 56 people were killed by Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) terrorists during their 1970s and 1980s terrorist campaign against Turkey, or the fact that most of the one million refugees from the fighting in Mountainous Karabagh are Azerbaijanis who fled conquering Armenians. Also, there may be some ill-judged memorial ceremonies, but Turkey does not have a “cult” of Talat Pasha, a probable principal architect of the Armenian genocide. As the authors themselves point out, the site of his grave in a small official memorial park for the Committee of Union and Progress leaders of late Ottoman times gets little official or popular attention.

Still, Marchand and Perrier state early on that their mission is not to write history, but to “give visibility to what has been erased … to gather together an antidote to the poison of denial … because impunity is always an invitation to reoffend”. And here they succeed to a remarkable extent, finding much that remains of Armenians, even as Turkey nears the 2015 centenary of when they were effectively erased from Anatolia: survivors, converts, crypto-Armenians, derelict churches, descendants of ‘righteous’ Turks, artisans’ tools in second- hand shops, flour mills, abandoned houses, songs and traditions. “Turkey”, they say, “is still haunted by the ghost of an assassinated people”.

Indefatigably, the authors travel to remote mountain villages and with President Gül to the Armenian capital for a football match that was part of the ill-fated late 2000s reconciliation process. They listen to the Armenians of Marseilles, France’s second city where 10 per cent of the population are descended from Armenians who fled Turkey, and explain why France and its parliament are so sensitive to the Armenian question. (They also suggest that some in the Armenian diaspora have constructed a counterproductive dream of a “fantasy Armenia, a promised substitute land”.) They interview the grand-children of a brave Turkish sub-prefect, Hüseyin Nesimi, who tried to stop the massacres in 1915, but was quickly assassinated near Diyarbakir, presumably at the orders of an alleged local organizer of the killings. They sit with the family of an Armenian citizen of Turkey killed by a far-right nationalist fellow soldier while on national service – on April 24, 2011. They slip into the mountains and show in a feast of detail how the spirit of the Armenian ‘brigands’ of yore lives on with the left-wing TIKKO group (Turkey’ Workers’ and Peasants’ Liberation Army, founded, you guessed it, on April 24).

In Sivas, they visit the last few rat-infested ruins in the once-thriving Armenian quarter. In Ordu, they find the old Armenian quarter rebaptised “National Victory”, and the old main church now turned into the mosque. In another town, an Armenian protestant church survived as a cinema and now an auditorium, with no sign of its provenance. Elsewhere, the dismantled stones of Armenian monasteries and houses have become the building material for new houses, sometimes with their religious symbols becoming decorative features. State ideology, they think, “even wanted to assimilate the stones”.

They join an Armenian guide who arranges tours for diaspora visitors to find the many souvenirs of Armenian-ness in eastern Turkey – and inhabitants who are not as hung up about their Armenian connections as might be expected. This picaresque explorer has tracked down 600 former Armenian villages, in some of which 1915’s survivors occasionally lived on for decades (the authors even stumble upon one during their travels). Other small Armenian communities “hidden, forgotten or assimilated” still live in thirty small or medium-sized towns. They show how village names have been changed and the memory of Armenians has been expunged. Very few people in Turkey are aware that the now iconic and ubiquitous signature of “K. Ataturk” was one of five models of signature dreamed up for the new republican leadership by a respected old Armenian teacher in Istanbul – whose son tells the story to the authors.

The authors discuss the impact of Fethiye Çetin’s 2009 book ‘My Grandmother’, which lifted the veil on Turkey’s many Armenian grandmothers, saved from the death marches to become servants or wives. In Turkey there are now, the authors believe, “millions of grandchildren of the genocide” who, because of the way Armenian-ness has been denigrated, have not wanted to be identified “more out of shame than fear”. In a province like Tunceli/Dersim, “it’s rare to find a family that doesn’t have an Armenian grandmother or aunt”. Shared saints’ days, common dances and music have blended into a new Armenian-Turkish-Kurdish mix in which it is hard to tell where one ethnicity ends and another begins. The book recounts touching scenes from Armenian churches as some of the descendants of Armenian converts try to return to the Armenian church and community. Indeed, the picture that emerges gives new meaning to the sign held up by many in the massive funeral procession in Istanbul for Hrant Dink: “We are all Armenians”.

Marchand and Perrier do not spare Turkey’s Kurds, who they say need to accept not just that there was a genocide but also recognize their part in plundering and kidnapping from the Armenian death marches. Still, a mainly Kurdish-speaking city like Diyarbakir has played a leading role in trying to make amends for what happened to the Armenians, rebuilding a church that had fallen into ruins, and bringing the language back into official use at a municipal level. Much of Diyarbakir actually used to belong to Armenians – more than one half, the authors suggest.

Indeed, the authors point out that many of Turkey’s grand companies today got their start in places where Armenian businesses had been forced out. Crucially for their argument of continued responsibility, appropriation continued into the republic, with the wealth tax that crushed the “minorities” in 1942 and the state-tolerated actions that took successive tolls on minority properties in the decades thereafter. (This continues: the front page headline of Tarafnewspaper today, 19 July 2013, is an angry denunciation of municipal plans to appropriate, knock down and redevelop the last stone houses of the abandoned old Armenian quarter in the eastern town of Muş). It’s not all grand state policy: they meet the family of an Armenian convert to Islam who came back from his years of military service to find that his lands had been peremptorily seized by his neighbours. There are harsh words about the energy that goes into the search for gold and valuables thought to have been hidden by Armenians as they were forced out of their homes: “pillaging is still today a national sport … a prolongation of the plundering.”

At first the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan looked as though it would lead Turkey out of this dead end. But it failed to see through normalization protocols with Armenia in 2009, and later it was Erdoğan himself who ordered the demolition of a monument to friendship with Armenia in the border town of Kars – on another 24 April. The authors give little credit to his government’s restoration of some Armenian churches and reinstatement of at least some Armenian property confiscated by the republic. Perhaps this reticence is because of the bad grace sometimes on display. At the reopening of the Armenian church of Akdamar on Lake Van, favorite of Turkish tourism posters, the envoy from Ankara managed to make a speech that mentioned neither the words “church” nor “Armenian”. Also, there were more than 3,000 active Armenian churches and monasteries in Anatolia before the First World War; now there are just six.

“Turkey and the Armenian Ghost” ends by conjuring up the changing spirit of the Armenian history debate in Turkey. This is largely thanks to the determination of Turkey’s academics since 2000-2005 to end what they knew to be an unacceptable and professionally untenable official policy and culture of denial. Clearly, it is real and trusted information developed by such experts at home, not the grandiose and sometimes hypocritical declarations by foreign legislatures, that has the best chance of changing the Turkish public’s mind. Marchand and Perrier’s stiletto-sharp impatience with the Turkish state’s slow pace or lack of official change may alienate many of those who most need convincing. But people can increasingly see more elements of what happened, and the deeply researched, convincing reportage in this book can help open up minds. “Of course it’s a genocide, but that’s a word that doesn’t work,” academic Cengiz Aktar tells the authors. “The only way to block the narrative of denial is to develop a policy of remembering, and to start the process of informing the population.”