Rescued and Saved: Armenian Genocide Survivors at Aleppo Reception Home

- (0)

The Genocide perpetrated against the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire was both gender-oriented and age-oriented. While the Armenian male population was generally killed before or at the beginning of deportation, women and children, as well as being massacred, were also subjected to different forms of physical, sexual and psychological violence. Children and young women were also forcibly transferred and incorporated into the enemy group. They were stolen, bought and sold, taken into slavery (also sexual), adopted, placed in state orphanages, different Muslim households (often in the homes of those who had killed their family members) with all the devastating consequences such practices imply. Armenian women and young girls (often children) were often forcibly married.

The practice of forced transfer and Islamization of young Armenian women and children was recognized in several post-World War documents. Article 4 of the Mudros Armistice which ended the hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies called for “All Armenian interned persons and prisoners [are] to be collected in Constantinople and handed over unconditionally to the Allies.”

Later, at the Peace Conference in Paris in 1919, the Allies established a “Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on Enforcement of Penalties” to investigate, among other things, the violations of the laws and customs of war. Its non-exhaustive list of 32 charges also included the abduction of girls and women for the purpose of forced prostitution (No. 6). The Commission also proposed the establishment of an ad-hoc tribunal for the trial of these offences, the jurisdiction of which was to be derived from the relevant provisions incorporated in the forthcoming peace treaty with Turkey.

Most importantly, the issue was raised in the lengthy Article 142 of the Treaty of Sèvres, which partly reads: “…the Turkish Government undertakes to afford all the assistance in its power or in that of the Turkish authorities in the search for and deliverance of all persons, of whatever race or religion, who have disappeared, been carried off, interned or placed in captivity since November 1, 1914…”

Thus, after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in WWI, a lot of individuals, as well as Armenian and international organizations became involved in the rescue of those Armenian transferee-survivors. Among them was the international post-war organization and predecessor of today’s United Nations—the League of Nations.

The League of Nations and Traffic in Women and Children

The League of Nations established a network of agencies to deal with issues of world concern such as disarmament, minority and health issues, etc. On the humanitarian agenda of the organization was the international trafficking in women and children (or white slavery as it was called before). As a result of the work of some international womens’ organizations, the trafficking issue was inserted as Article 23c of the League of Nations’ Covenant, which reads in part:

“Subject to and in accordance with the provisions of international conventions existing or hereafter to be agreed upon, the Members of the League: …(c) will entrust the League with the general supervision over the execution of agreements with regard to the traffic in women and children, and the traffic in opium and other dangerous drugs.”

The two categories of women that the League of Nations dealt with in this article were “women who work abroad as prostitutes, and women dislocated because of various political and military circumstances.” Interestingly also, for most purposes the League classified women and children in the same category defining them as “requiring special treatment and extra protection.”

On the basis of Article 23c the League of Nations became involved in the issues of deported Armenian women and children in the Near East.

In June-August 1920, a pamphlet The Liberation of non-Mohammedan Women and Children in Turkey about the treatment of Christian women and children in Turkey during WWI was circulating in the League of Nations, having been received from the National Vigilance Association and International Bureau for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic. Another application was made from the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. In her letter addressed to the League of Nations, suffragist Helena Swanwick (1864–1939) offered to create a special Commission of the League of Nations on the issue of the enslavement and dishonoring of women and children in the East as a result of the war.

The issue of the Traffic in Women and Children was considered by the 2nd Committee of the League of Nations. The Committee unanimously adopted two draft resolutions, the second one dealing more specifically with the case of the deportation of women and children that rose out of WWI, when some of the deported women, especially the Armenian women, but also Greek and Syrian women and women of other nationalities had been in captivity since 1915. The practice was described as “worse than slavery.”

As a result of these developments, on December 15, 1920 the Assembly of the League of Nations invited the Council “to constitute a Commission of Enquiry with a view to informing the Council as to the present situation in Armenia, in Asia Minor, in Turkey, and in the territories adjourning their countries regarding deported women and children.” The League nominated the three best qualified persons residing in the districts in question. It was decided to start the enquiry in “that part of the Turkish State at present under the jurisdiction of the Constantinople Government” and gradually extend it, working in close cooperation with the Allied High Commissioners in Constantinople. In addition, the member-state governments were obliged to provide every possible assistance and all relative information. Dr. William Kennedy, Emma Cushman and Madame Gaulis, who was later replaced by Karen Jeppe, were nominated as members of the Commission. The Commission opened its headquarters in Aleppo (Jeppe) and Constantinople (Kennedy and Cushman).

The Aleppo Rescue Home

The Aleppo branch of the Enquiry Commission carried out the rescue and rehabilitation of the Armenians held in Muslim captivity in the French zone of occupation. According to Jeppe, 30,000 Armenians were in bondage in that region. The Aleppo Rescue Home or Reception House was situated in the northern outskirts of Aleppo. It was established first by the American Near East Relief organization in 1918 and then administered by the League of Nations. With the help of its agents and several stations established in different parts of the region (Djirablous, Ras al-Ayn, Mardin, Deir el-Zor, Hasitche, Rakka, Bab, Arabpounar, etc.), Jeppe was able to shelter in the Reception House thousands of Armenians rescued from Muslim captivity.

The task of rescue was not an easy one. Nomadic people of the region were generally reluctant to free their Armenian captives. After a long passage of time, Armenian survivors were sometimes also reluctant to leave the Muslim “homes” because of children born to Muslim fathers, security concerns, fears about fleeing and the awareness that no Armenian was left alive. Others were afraid of admitting their Armenian identity because of fear of the repetition of 1915’s events or punishment.

Little children were raised as Muslim and sometimes didn’t even know their real identity. However, there were many who, after hearing about the rescue missions, left their “prisons” willingly.

Jeppe succeeded in liberating thousands of Armenians not only from Arab Bedouins, but from neighboring Turks and Kurds. Liberation or rescue was performed through negotiation, bribery, kidnapping or urging the Armenians to flee by themselves. Usually they were ransomed by their rescuers, at a rate of 0,50-2 Turkish gold (rarely the amount reached 10 Turkish gold) depending on the territory.

Liberated Armenians were admitted to the Reception Home where their details were registered and their names sent to newspapers, churches and Armenian unions in order to find their relatives. Meanwhile, the inhabitants of the Reception House were taught different crafts in order to become self-supporting. New identity documents were obtained for the liberated Armenians and steps were undertaken to bring them back to Christianity.

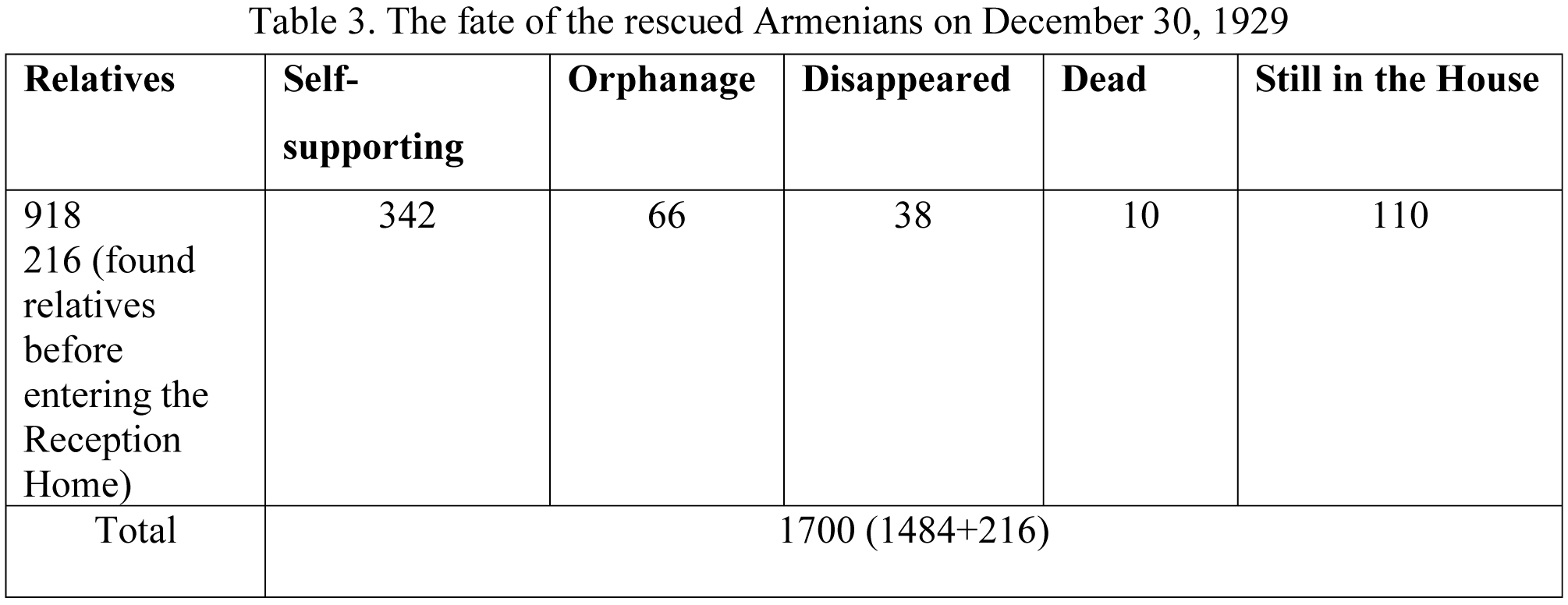

As a League of Nations Commissioner (from March 1, 1922 to December 31, 1927), Karen Jeppe succeeded in rescuing 1,484 Armenians. Most of them also entered the Reception House, and others were rescued without being registered.

In her words: “Sometimes, we have helped their relatives to find them, and the direct expenses having been covered by the relatives, the rescued did not enter our lists. In other cases the rescued found and joined their relatives, before they reached our home, and they too were not filed. I estimate the number of these rescues to exceed 200, so that the total of our rescued under the auspices of the League of Nations amounts 1700.”

After December 31, 1927 in her private capacity Karen Jeppe rescued another 180 Armenians.

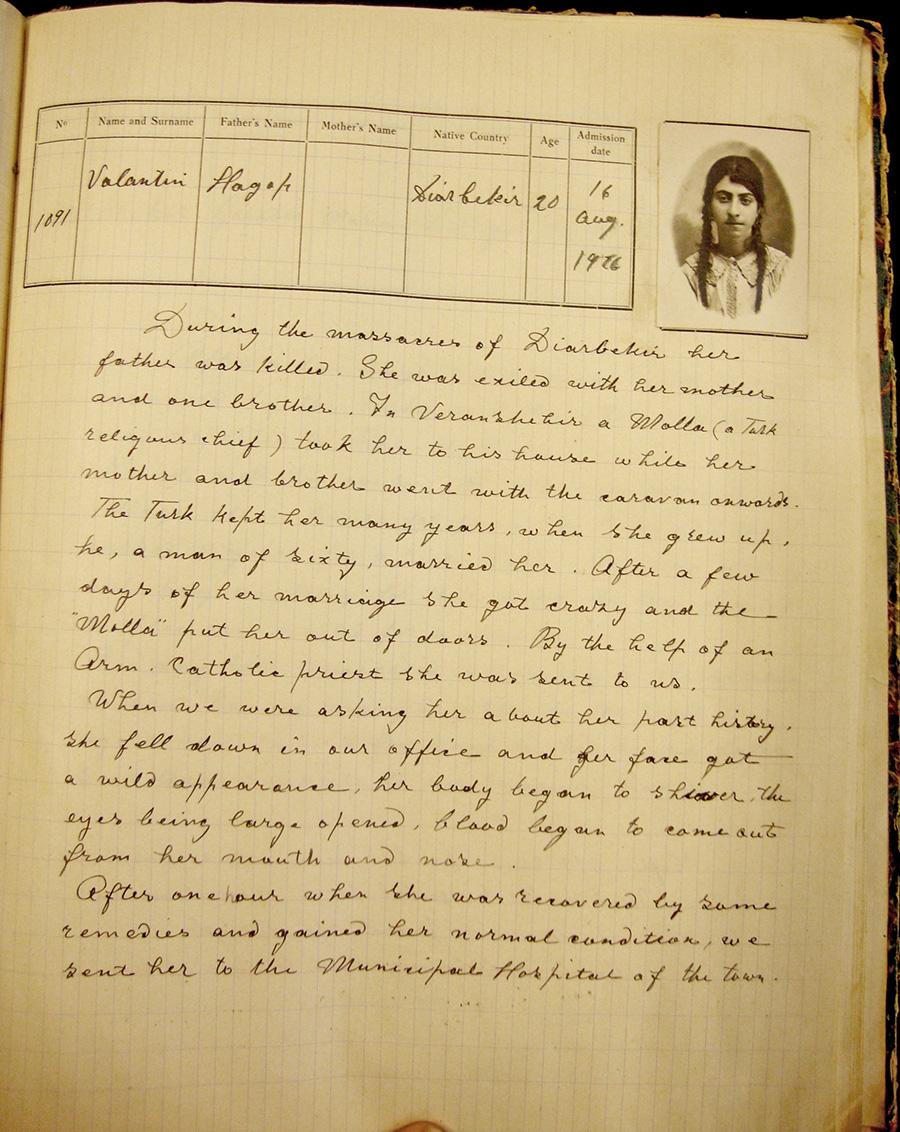

The liberated Armenians were interviewed and each interview was registered in a notebook. Those surveys include a photograph of a rescued person and some biographical data (parents’ names, place of origin, age and date of admission to the Reception House). This was followed by a short life-story mainly about the 1915 events, captivity and rescue. The fate of the rescued Armenians was recorded on the back of the paper.

During the massacres of Diyarbekir her father was killed. She was exiled with her mother and one brother. In Veranshehir a Molla (a Turk religions chief) took her to his house while her mother and brother went with the caravan onwards. The Turk kept her many years, when she grew up, he, a man of sixty, married her. After a few days of her marriage she got crazy and the “Molla” put her out of doors. By the help of an Armenian Catholic priest she was sent to us. When we were asking her about her past history, she fell down in our office and her face got a wild appearance, her body began to shiver, the eyes being large opened, blood began to come out from her mouth and nose. After one hour when she was recovered by some remedies and gained her normal condition, we sent her to the Municipal Hospital of the town.

Left 8/9/26. In the municipal hospital, Aleppo. Went to the hospital for an accouchement and never was found afterward. We do not know what became of her.

In the beginning of the Great War his father was a soldier in the Turkish army; he never gave any news and never came back. Babo believes that he died.

The day of their deportation a Turk of the town came and took the mother with her child out of the caravan and brought them to his house. He immediately violated the woman and took afterwards Babo outside the town. From a bridge he threw Babo into the river in order to kill him. Babo did not die he fled into the mountains and kept hidden in the forests for several months eating only grasses.

At his small age he had to go from village to village in order to earn his living. He became at last an assistant … driver and came in this way to know the way to Syria.

Once he met 2 Armenian boy of his age. They talked together and made their plan of escape. All of them had suffered much from the Turks. They fled and succeeded, we took them in.

Left for Beyrouth 20-7-28 Self-supporting

The number of females over the age of 15 rescued from captivity was less than (463) the number of rescued males (591). According to Jeppe, the national feelings of Armenians, especially of Armenian boys, were quite strong, and they became powerful mainly at an age when they realized their true origin. The high number of rescued boys can be explained by different physical and mental factors. Of course, they were physically stronger and had better chances to survive the hardships of captivity and slavery, as well as when fleeing their Muslim homes. The young men also experienced the absence or relatively low level of socio-physiological bonds; they were usually mistreated and served as shepherds or slaves. For women, fleeing was a more difficult experience as sexual and physical violence, bondage in new families, children born of their new husbands and inability to leave their children were all factors that deterred and blocked their escape. There also was a fear of stigma which would prevent them from reintegrating into Armenian society.

The interviews of the rescued Armenians revealed consistent stories of deportations, massacres, rapes, physical and sexual violence, forced transfer, followed by years of servitude, forced marriages, etc. These eyewitness testimonies represent and affirm the organizational pattern of the Armenian Genocide. The majority of accounts start with describing the fate of the Armenian male population in 1915 – how those conscripted to the Ottoman Army were later killed or worked to death in the working battalions and how the remainder were later collected and killed in their native towns or separated and massacred on the deportation routes.

The stories of the arrests and massacres of Armenian intellectuals can also be found in the files. The deportation of the general Armenian population, consisting mainly of women and children, is mentioned in all accounts. The rescued Armenians describe how dreadfully they suffered on the roads under the burning sun, from hunger, thirst and exhaustion; many died from typhus, dysentery and other illnesses. Deportation caravans were constantly attacked by Turks, Kurds and Arabs who, after robbing deportees, killed or wounded most of the unfortunate people, violated women and children, threw them into the river or massacred them.

Many survivors were taken as slaves or servants; women and girls were forced into marriages. Guarding gendarmes collected beautiful girls from the caravans and sold them to Turks and Kurds or even gave them away as gifts. According to one account, a Sheik from Djebour bought 12 Armenian girls. Sometimes young Armenian women and children witnessed the slaughter of their family members later to be dragged into the house of the murderer and forced to live with him.

A number of accounts also affirmed that the Turkish government collected Armenian children and distributed them in state-run orphanages.

After enduring the sufferings and horrors of genocide, witnessing the massacre of their families and nation, being physically and sexually violated, many survivors suffered from some mental problems. Some women suffered from syphilis and miscarriages. According to Jeppe, out of the thousands of Armenian females she had come into contact with, all but one had been sexually abused.

Many Armenian women were willingly leaving their Muslim husbands and children to return to their Armenian roots. There were also those (very few) who returned to their Muslim husband, unable to endure the separation. Interestingly, some Armenian women fled with their children born to Muslims.

The surveys also dwelled upon the ways the Armenians discovered their origins. Many survivors were too young at the time of deportation to remember anything about their families and identity, so relatives or surviving Armenians from the same district told them about their Armenian origins. Very often the following similar story is found in the accounts: Muslims often called him/her ‘giaur’/’giour’ and when interested about the meaning of the word, they found out about their Armenian origins. Very often the expression “Christian dog” appears in the accounts. A number of stories reveal that Armenian mothers when forced to marry Muslims told their children that they were Armenians and Christians.

A huge national campaign was launched after the Armenian Genocide, which the Aleppo Rescue Home joined. In this enterprise the crucial role of Armenian men should be highlighted, who despite the patriarchal nature of Armenian society and existing traditions, accepted back their abducted and violated wives or married other saved Armenian women. There were a lot of marriages among the inhabitants of the Rescue Home, and Jeppe made a great contribution to that.

The admission files of the Aleppo Rescue Home are some of the first eyewitness testimonies about the Armenian Genocide representing the horrible experiences of the Armenians. Although many Armenians were rescued, reclaimed and rehabilitated in the Aleppo Rescue Home, thousands of Islamized Armenians remained in Muslim households and institutions.

The Armenian Weekly