Monumental Book on Khatchkars (Cross Stones) Presented at New York’s Zohrab Information Center

- (0)

By Florence Avakian

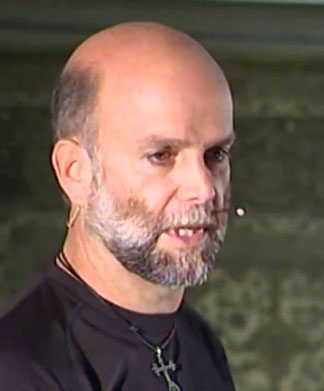

ZOHRAB INFORMATION CENTER, NY –The year 1993 was a life-changing year for Hrair Hawk Khatcherian. That year, he was told that he had lung cancer and had only 10 days “to die”. Subjected to unbearably painful treatments in the hospital, he had placed on his hospital room wall a cross and photographs of Armenia and Artsakh (Karabakh).

“It was by staring at them fiercely, day by day, with my mortally wounded hawk’s eyes that I succeeded in tearing myself from the claws of death, to take flight again, and to rise high in the sky in the direction of my true destiny,” he revealed. It marked the beginning of a unique mission for him.

Promise to God

Since that crucial year, Khatcherian made a solemn promise to God that he would photograph khatchkars around the world. “My approach comes from the biblical, faith and soul-filled side of my life. The story of khatchkars is to bring humanity back to heaven.”

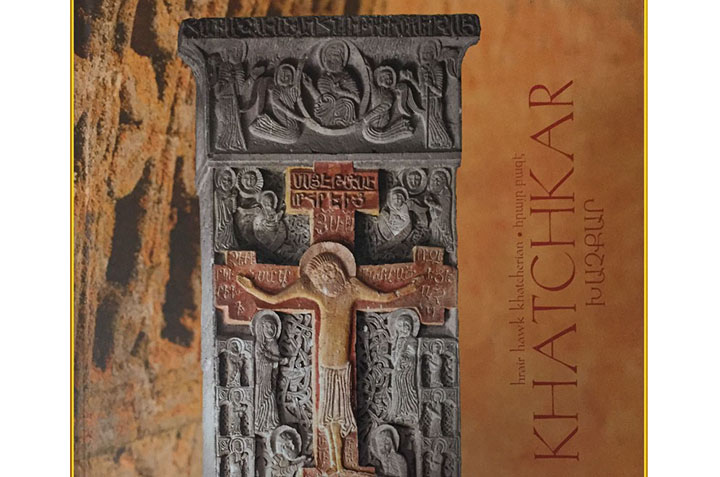

And so began a 24-year grueling journey involving “research, planning, cars, boats, airplanes, helicopters, cameras, reflectors, tripods, cameras, flash and tape measure.” The result became a monumental published book, entitled Khatchkar.

On Monday evening, March 30, the acclaimed photographer presented an engrossing lecture replete with dozens of slides from this unique album to a large and enthusiastic crowd, at the Zohrab Information Center of the Armenian Diocese in New York.

And in Hawk Khatcherian’s own words, this herculean work of the Christian art form “is a book that will never be completed,” related Fr. Daniel.

“Khatch means cross in Armenian,” said Hrair Hawk Khatcherian, starting his fascinating talk. “Born with a predestined family name of Khatcherian, I could not help but witness and photograph khatchkars, (stone-carved crosses).”

For Khatcherian, this life’s work has been a soulful pilgrimage of 24 years to 45 countries, encompassing “Christ, heaven, hell, earth, cow dung, mud, rain, hail, clouds, and sun.” These travels included Armenia, Artzagh, historic Armenia, Cilicia, Iran, Georgia, Lebanon, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Crimea, Venice, and museums worldwide.

Danger Zones

Many times, these trips were in dangerous militarized areas, including near the Azerbaijani border, and at the base of Mt. Ararat which had been mined by the Turkish government. Often, he walked for three to four hours in muddy forests, or rock strewn cliffs, in freezing cold or brutally hot weather, sometimes going back to the same spot many times to catch the right light, or wait until the rain or snow had subsided.

In Jerusalem, he perfected his climbing skills, borrowing a ladder spanning two floors high to get the correct angle of a khatchkar imbedded in the cupola of a church.

“”These khatchkars did not happen overnight,” he related. “The master carvers dedicated their art and creativity for important events and victories, even for the birth of a village, an ordinary child’s birth, for the fertility of crops, for rain, or for the health of a sick person,” he said, adding that on some stones secret messages were inscribed.

Christ and Mother Mary were dominant subjects, and the themes of angels, eagles, lions, oxen are repeated again and again on these art forms. From the 13th century on, Christ is never shown crucified, with a few rare exceptions. He is depicted at the top of the plaque, in a triumphal way.

Commenting on some of the areas, he said that the khatchkars in Artzagh were “more down to earth, natural and unique, with the tallest (some 12 feet high) found in the Dadivank church in the remote and scenically beautiful Kelbajar region of Artsakh. They were so tall because centuries ago, the area was home to some of the royal princes of the Armenian homeland.

In Kars, khatchkars had been used as masonry, and in Van used as steps for defense. In Nakhichevan, now under the control of Azerbaijan, they were employed to build train tracks. In Nakhichevan’s Julfa cemetery, the biggest in all of Armenia’s history, and where several thousands of khatchkars still stood, the cemetery was completely destroyed in 2002 and 2005 by the local Azerbaijani authorities.

The khatchkar, distinguished by the originality of its appearance, and dominated by the image of the cross, symbolizes the Tree of Life. Its particular scale is particularly striking, and goes back over one thousand years, surviving to the present day, not only on Armenian territories not systematically destroyed, but also in diasporan communities.

Patrick Donabedian of Aix Marseille University has written, “While embodying a strong national and religious identity, the art of Khatchkars, probably the most iconic example of Armenia through the ages, demonstrates a large openness to the outside world, and a great faculty of exchanging and sharing. It is definitely the opposite of the hatred it is sometimes the victim of.”

Today, in excellent health, Khatcherian whose photographs encompass 14 unique albums, “lives only for his family (wife and two teenage children), Armenia, Artsakh, and the fundamental and exceptional benchmarks of the Armenian world.”