Lemkin’s Armenian Collaborators and the Genocide Convention:

- (0)

‘With the Ink of Their Blood’

By Dr. Khatchig Mouradian

The Armenian Weekly

While it has become widely accepted in recent years that the World War I destruction of the Armenians influenced Raphael Lemkin’s work, the efforts of Armenians in support of Lemkin’s campaign to secure the adoption of the Genocide Convention and its ratification by parliaments around the world have received little attention. In this article, part of a larger project, I explore the role of the Hairenik newspapers in this effort, focusing on three of Lemkin’s close collaborators: editors James G. Mandalian and Reuben Darbinian and correspondent Levon Keshishian.1

From Nemesis to ‘Genocide’

In the absence of a Nuremberg trial equivalent for the Armenian massacres, the survivor generation also took justice into its own hands. Trials were held in Allied-occupied Istanbul sentencing perpetrators to death in absentia, but most Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) leaders were beyond reach, having fled the country (many to Germany), while those the British had imprisoned in Malta were released as part of a prisoner exchange deal. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) decided in 1919 to assassinate the perpetrators. By 1922, the ARF had gunned down Ottoman Turkish leaders implicated in the genocide in Berlin, Rome and Tiflis: Interior Minister Talaat Pasha, Ottoman Grand Vizier Said Halim Pasha; Minister of Navy Cemal Pasha; CUP founding member Bahaeddine Shakir; and Trebizond governor Cemal Azmi. The project, dubbed “Operation Nemesis,” made headlines around the world2, influencing a Polish-Jewish university student named Raphael Lemkin to pursue the task of establishing an international law against attempted annihilation of ethnic groups.

Reading about Talaat Pasha’s murder in newspapers in 1921, Lemkin felt that Soghomon Tehlirian, the Operation Nemesis assassin, “upheld the moral order of mankind”:

But can a man appoint himself to mete out justice? Will not passion sway such form of justice and make travesty of it? At that moment, my worries about the murder of the innocent became more meaningful to me. I didn’t know all the answers but I felt that a law against this type of racial or religious murder must be adopted by the world.3

Lemkin’s search for answers culminated in the coinage of the term “genocide” in 1943 and his lifelong struggle to pass a law against it. Two months after the third count of the Nuremberg Indictment stated that defendants had “conducted deliberate and systematic genocide,” the Armenian-language daily newspaper Haratch in Paris published an editorial providing the readers with background on the term “génocide,” using information from the French newspaper Le Monde. “A new word was used in the Nuremberg trials, which means Tseghasbanutyun,” founding editor of Haratch, Shavarsh Missakian, wrote. He then referred to Lemkin’s efforts toward punishment and prevention and lamented:

We read these lines, we follow the Nuremberg trials, and our mind instinctively wanders to a faraway world, where “war crimes” took place thirty years ago … Where were the jurists and judges back then? Had they not discovered the word, or was the blood-thirsty monster so powerful or unreachable that they could not punish him?4

After the UN General Assembly adopted the Genocide Convention in December 1948, the Hairenik Weekly in Boston published an editorial that argued, “To have any meaning at all, the decision to outlaw genocide must go deeper. It must also offer remedy to the wronged parties. To outlaw genocide, but to sanction the basic aims and results of the action is only a half measure.”5

Levon Keshishian

Although this was the dominant sentiment in the Armenian press from the Middle East to North America, Armenians around the world strove to secure the adoption of the Convention at the UN, and then its ratification by parliaments around the world. Lemkin recounted how:

“[T]he Armenians of the entire world were specifically interested in the Genocide Convention. They filled the galleries of the drafting committee at the third General Assembly of the United Nations in Paris when the Genocide Convention was discussed. An Armenian, Levon Keshishian, the well-known UN correspondent for Arab newspapers, helped considerably through his writings in obtaining the ratifications of many Near Eastern and North African countries.6

Keshishian and Lemkin first met after the UN adopted the Genocide Convention.7 Here’s how Keshishian describes the encounter:

Lemkin is a law professor, divides his time between Boston, New York and Washington. My meeting with him was short, but it was most interesting. He wanted to see the Arab News Agency. He asked, are you the same Levon Keshishian of “Hairenik Weekly.” I replied yes. He then confesses that the “Weekly” has been one of the outstanding newspapers supporting the Convention of Genocide and paid full credit to editor Mr. James G. Mandalian. Then coming to the point, he said, “You are an Armenian.” After a long pause he said: “You will therefore understand how important this Convention is.”8

Keshishian filed dozens of reports in Middle Eastern in North American publications when parliaments ratified the convention, when Lemkin delivered lectures and made public statements, and even when he privately advocated for the Convention. He also connected Lemkin to political figures in the Middle East and beyond and then reported on Lemkin’s communication with them. Keshishian reported, for example, about how “Prof. Rafael Lemkin, father of ‘genocide’ has written to Lebanese deputy Dicran Tosbath (Armenian) asking him to work for the ratification of the Convention of Genocide by the Lebanese Parliament.”9

Hairenik editors Mandalian and Darbinian

Reuben Darbinian and James G. Mandalian, the editors of the Hairenik Daily and Hairenik Weekly respectively, had an even longer history of collaboration with Lemkin.10 Their correspondence with the Father of the Genocide Convention dates back to the late 40s and offers insight into how Lemkin mobilized thought leaders in communities affected by genocide to advocate for the ratification of the Convention by the US Congress and parliaments around the world.

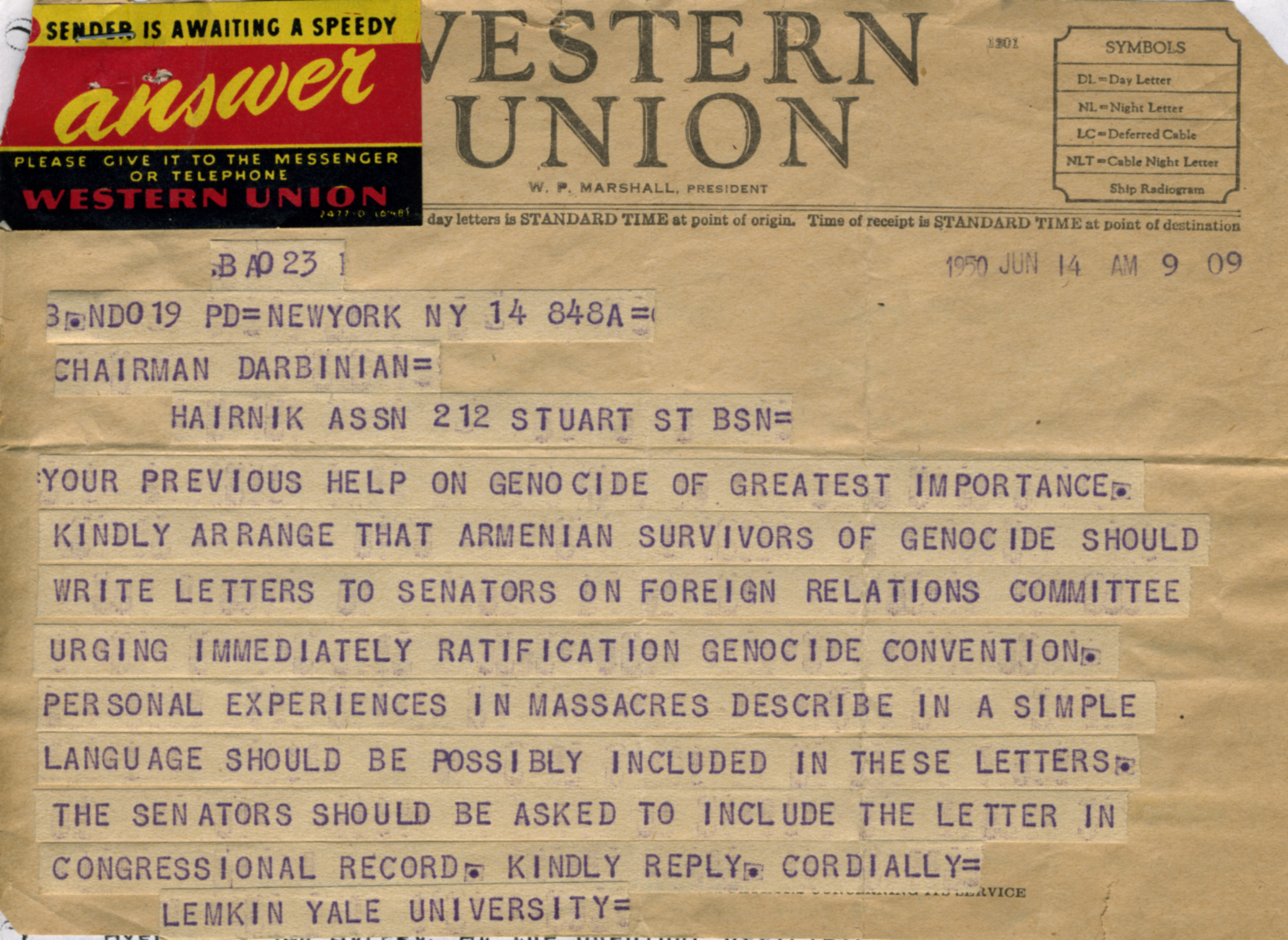

In a telegram to Darbinian in June 1950, Lemkin noted that the Hairenik editor’s “previous help on genocide [was] of greatest importance.” He then requested that Darbinian “kindly arrange that Armenian survivors of genocide… write letters to Senators on Foreign Relations Committee urging immediate ratification [of] Genocide Convention.”11

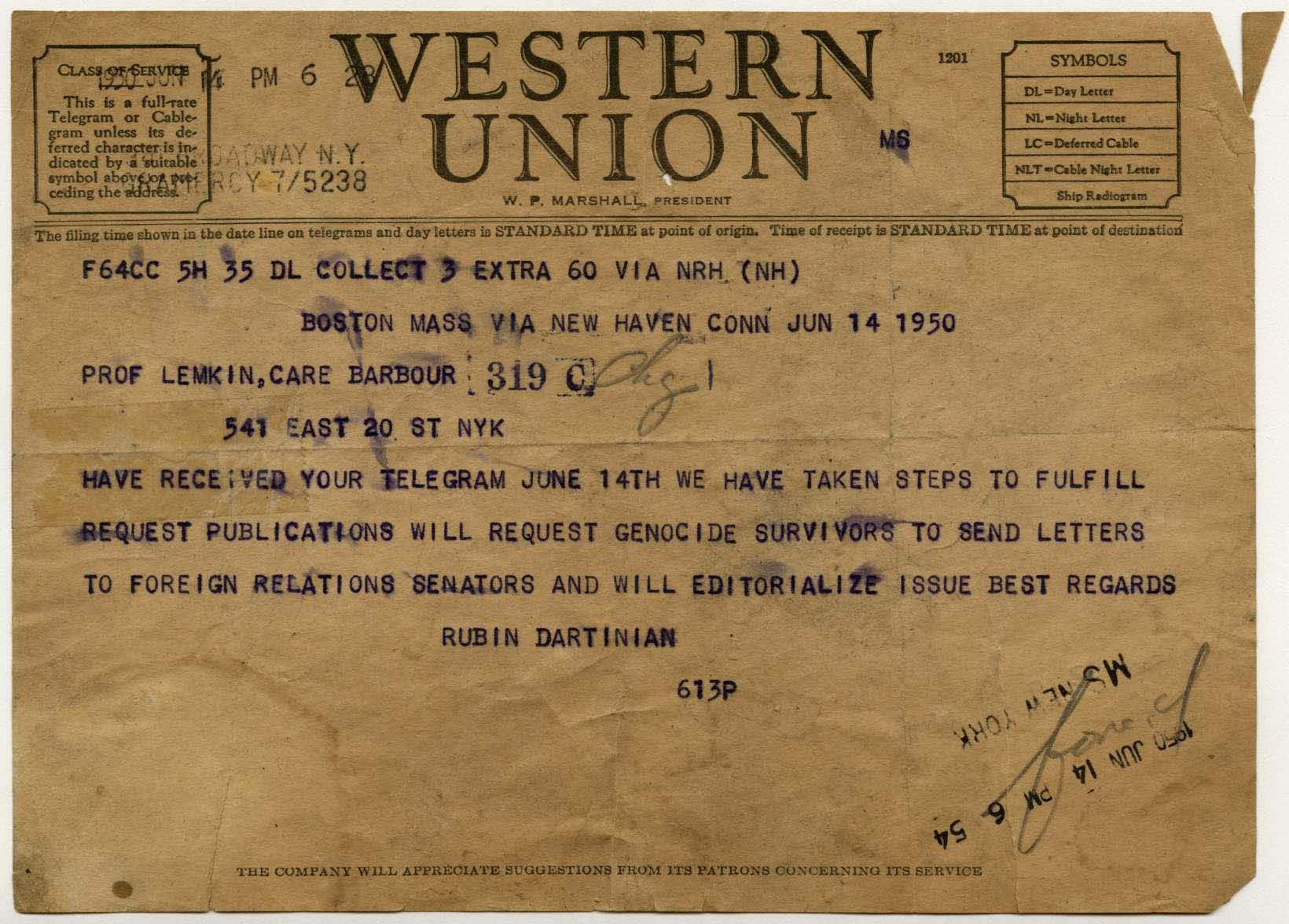

Darbinian responded, “We received your telegram… We have taken steps to fulfill request…. Will request genocide survivors to send letters to Foreign Relations Senators and will editorialize issue.”12

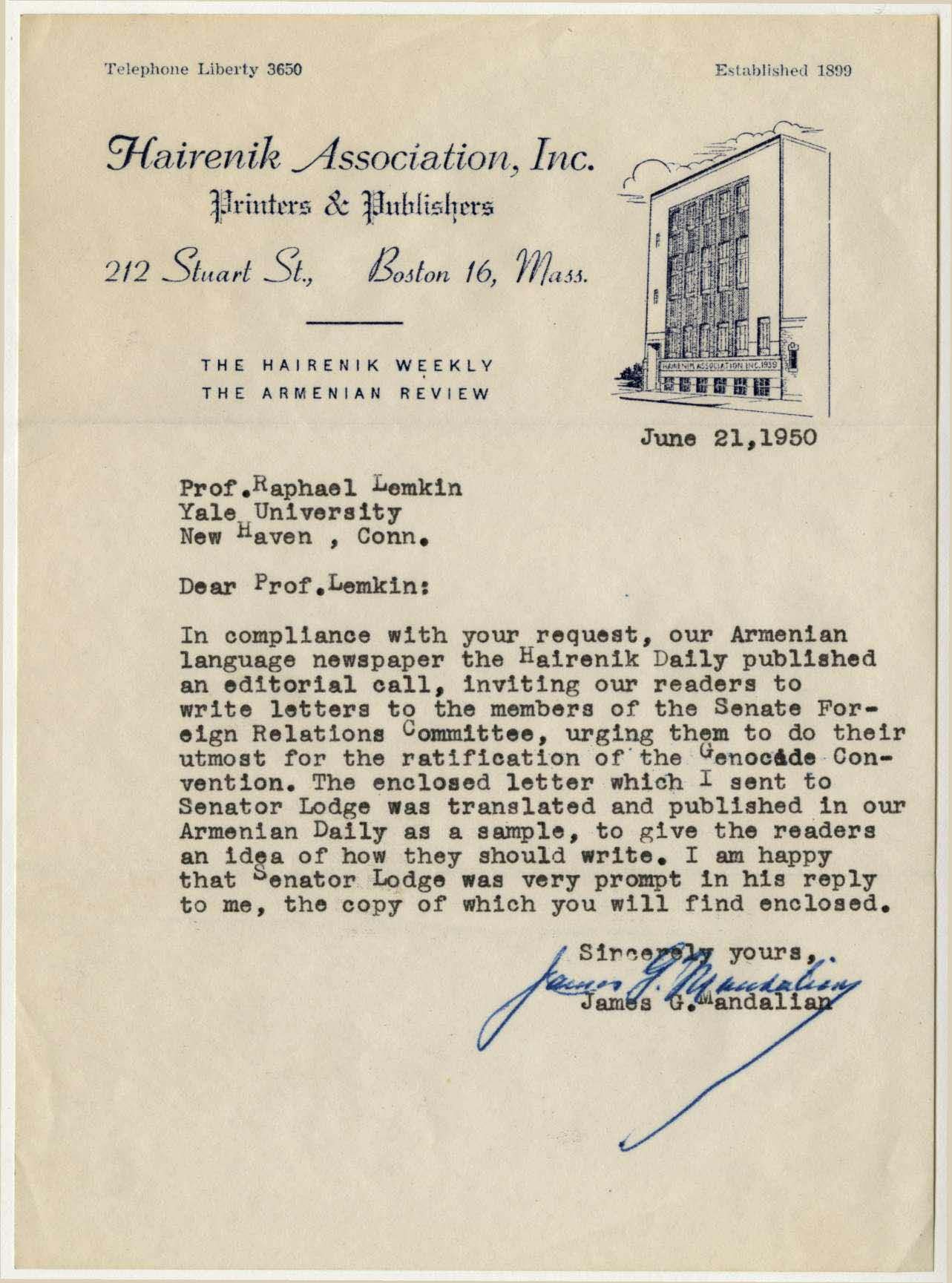

A week later, Mandalian wrote a letter to Lemkin in which he said:

In compliance with your request, our Armenian language newspaper the Hairenik Daily published an editorial call, inviting our readers to write letters to the members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, urging them to do their upmost [sic] for the ratification of the Genocide Convention. The Enclosed letter which I sent to Senator Lodge was translated and published in our Armenian Daily as a sample, to give the readers an idea of how they should write. I am happy that Senator Lodge was very prompt in his reply to me, the copy of which you will find enclosed.13

On 12 November 1953, the Hairenik Weekly published yet another editorial arguing for US Congressional ratification. “In the face of known facts it is difficult to understand the precise motive which underlies this hesitation [to ratify the Convention].”

The editorial went as far as to say that the US has never committed any genocidal act:

It cannot be contended that the United States suffers from a guilty conscience. The United States has never been guilty of a genocidal act. On the contrary her entire history is a record of abhorrence of all which is inhuman, brutal, and barbaric. And yet, this very country which initiated the genocide convention, which is supposed to lead the nations of the world in the fight against the forces of tyranny, is the very one which has to be coaxed and urged to subscribe to a civilized measure.14

The United States would not be “coaxed” in Lemkin’s lifetime.

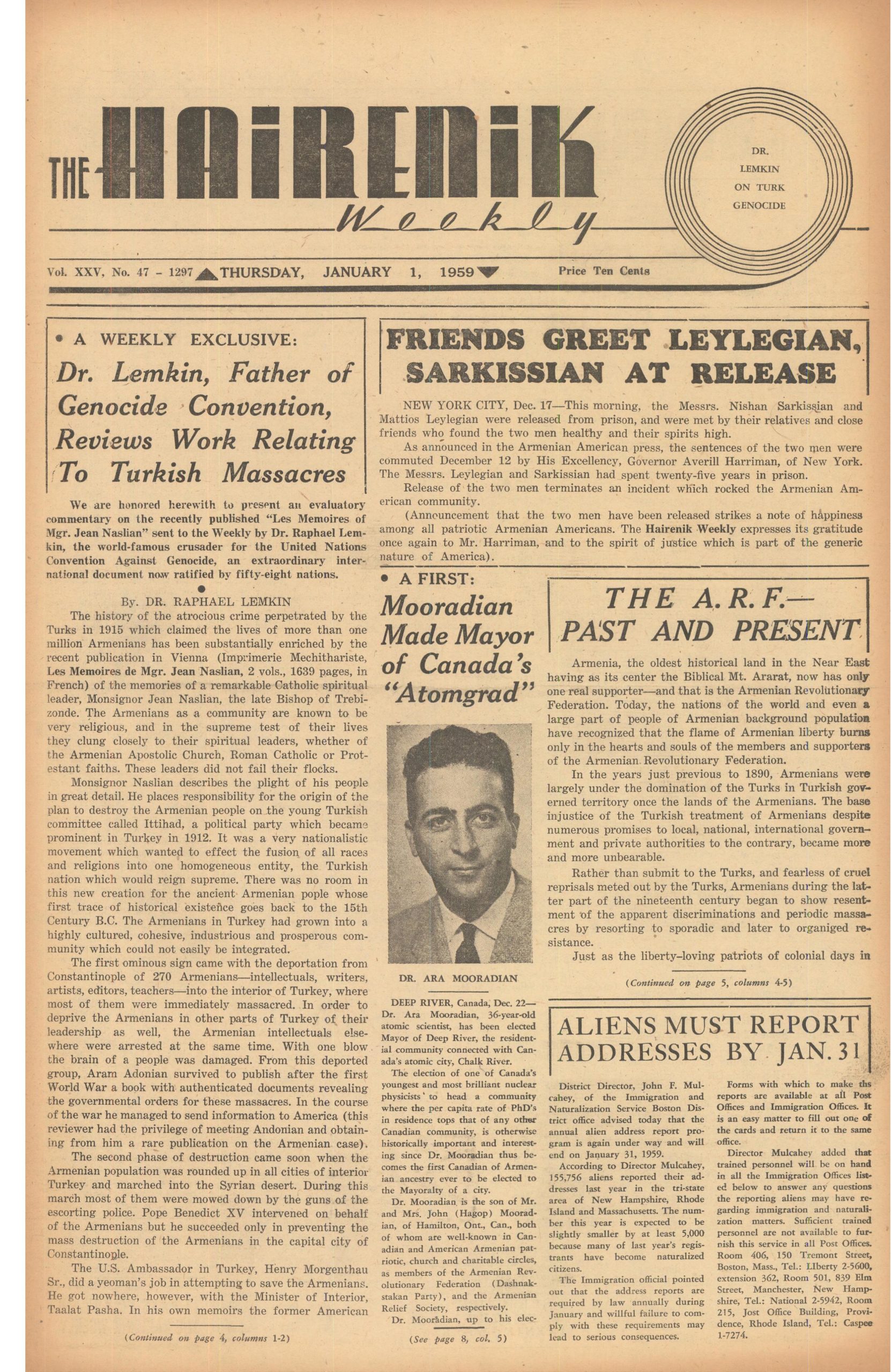

A few months before he died, Lemkin penned an article for the Hairenik Weekly, in which he said, “The sufferings of the Armenian men, women, and children thrown into the Euphrates River or massacred on the way to Der-el-Zor have prepared the way for the adoption for the Genocide Convention by the United Nations and have morally compelled Turkey to ratify it.”

He added, “One million Armenians died, but a law against the murder of peoples was written with the ink of their blood and the spirit of their sufferings.”15

Lemkin continued working with Armenian leaders to secure the United States’ ratification of the convention until his death in August 1959. US ratification only came in 1988. But with the 50th anniversary of the 1915 nearing, Lemkin had equipped Armenians, primarily in the diaspora, with a powerful weapon to push for justice.

The Armenians, who had helped Lemkin attain the ratification of the Convention by legislatures around the globe, now engaged in yet another struggle: a decades-long battle for the acknowledgement of the Armenian Genocide.

_________________

1 This article is partly based on a lecture delivered at NAASR in 2011. For a biography of Raphael Lemkin and his campaign for the Genocide Convention see, for example, John Cooper, Raphael Lemkin and the Struggle for the Genocide Convention (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). For Lemkin and the Armenian genocide, see Steven L. Jacobs, “Raphael Lemkin and the Armenian Genocide,” in Richard G. Hovannisian, ed., Looking Backward, Looking Forward: Confronting the Armenian Genocide (New Brunswick: Transaction, 2003), 125–135; Samantha Power, “A Problem from Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide (New York: Basic Books, 2002); and Peter Balakian, “Raphael Lemkin, Cultural Destruction, and the Armenian Genocide,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 27:1 (Spring 2013), 57-89.

2 I recently curated a selection of newspaper clippings about Talat’s assassination for the Armenian Weekly.

3 Donna-Lee Frieze, ed., Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 2013), 20.

4 “Editorial,” Haratch newspaper, 9 December 1945, 1

5 “Editorial: Exit Genocide,” The Hairenik Weekly, 30 December 1948, p. 2.

6 “A Weekly Exclusive: Dr. Lemkin, Father of Genocide Convention, Reviews Work Relating to Turkish Massacres,” The Hairenik Weekly, 1 January 1959, 4 (continued from page 1).

7 The two had several other meetings in the 1950s. See, for example, “Leaders of ANCHA Visit UN Official,” The Hairenik Weekly, 12 November 1953, 2.

8 “Honduras is 35th Nation to ratify Genocide, but Life of Convention is Menaced,” The Hairenik Weekly, 13 March 1952, p. 3 (article continued from page 1). For more reporting by Keshishian on the Genocide Convention see, for example, Keshishian’s column “This and That from New York,” The Hairenik Weekly, June 5, 1952 and 20 August 1953, p. 3;

9 “This and That from New York,” The Hairenik Weekly, 28 August 1953, p. 2. Lebanon ratified the convention a few months later. The Weekly reported the news on its front page. “Lebanon is 43rd Nation to OK ‘Genocide,” The Hairenik Weekly, June 5, 1952 and 7 January 1954, p. 1.

10 Darbinian served as the editor of Hairenik Daily for more than four decades. Mandalian was the first editor of the Hairenik Weekly, as well as a founder and first editor of the Armenian Review.

11 Telegram from Lemkin to Reuben Darbinian, then the editor of the Hairenik newspaper, dated 14 June 1950. Haigazn Khazarian Archive, National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR) Mardigian Library.

12 Telegram from Darbinian to Lemkin, dated 14 June 1950. Center for Jewish History, Raphael Lemkin Collection, Box 2, Folder 3.

13 Letter from James G. Mandalian to Lemkin, dated 21 June, 1950. Center for Jewish History, Raphael Lemkin Collection, Box 2, Folder 3.

14 “Editorial: The Genocide Convention,” The Hairenik Weekly, 12 November 1953, 2.

15 “A Weekly Exclusive: Dr. Lemkin, Father of Genocide Convention, Reviews Work Relating to Turkish Massacres,” The Hairenik Weekly, 1 January 1959, 1.