Interview: Pulitzer Winner Balakian’s World of Poetry

- (0)

By Nanore Barsoumian

Writer Peter Balakian grapples with a world of complexity and paradox in his latest book of poetry, Ozone Journal (2015), which won him a Pulitzer Prize two weeks ago. “[Poetry] is a transformed and compressed piece of language,” he says in a phone interview with the Armenian Weekly. “That’s what poets do; we’re obsessed with phrases and the nuances of linguistic music.”

Balakian became the second Armenian American to claim the award in the field of literature. In 1940, beloved Armenian American author William Saroyan was awarded the coveted Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Crossing time, space, and cultures, Balakian has created a multi-dimensional reality and space that belongs to all and none, where the past offers a respite from the present, but only for a fleeting moment.

“I see Ozone Journal as a very transnational work. My imagination moves across borders and continents, from the slums of Nairobi to the Turkish Armenian border, to the Syrian Desert, to the Native American southwest, to the urban ruin of a great American city like Detroit,” he says.

For Balakian, poetry is an “invention”—deliberate, precise, and also metaphysical when it can be. “Poetry is a foray into truth, a human experiential truth,” he muses.

Poet David Wojahn writing in Tikkun Magazine had this to say about the poet’s latest work: “Balakian’s project of ‘writing horizontal’ attempts to find within the pitiless hubbub of contemporary consciousness those essential recollections (what Wordsworth termed ‘spots of time’) that are the sources of selfhood and to devise a new method for meaningfully confronting and memorializing the past.”

On April 18, Mike Pride, the administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, announced, “In poetry, for a collection of poems that bear witness to the old losses and tragedies that lie beneath a global age of danger and uncertainty, the prize goes to Ozone Journal by Peter Balakian.”

Writing, revising, rewriting—the third draft become the seventh, the hundredth, and perhaps only then will Balakian feel satisfied and move to the next.

Ozone Journal, published by the University of Chicago Press, is a sequel to his acclaimed “A-Train/Ziggurat/Elegy” (2010).

Balakian is the Donald M. and Constance H. Rebar Professor of the Humanities at Colgate University. He has authored seven books of poems and four prose works, including the New York Times bestselling The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response, and Black Dog of Fate, a memoir and winner of the PEN/Albrand Prize.

***

Nanore Barsoumian—Talk about your journey with poetry.

Peter Balakian—I began writing in college, especially after I quit my life as a football player. I quit that world and plunged into academic study and began writing poems in the middle of my college years. My life as a poet really started then. It’s been my fundamental orientation. I’ve always first been a poet; that’s where I live.

As a young poet, I came out of an American poetic tradition that was defined—in different ways—by Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, and Robert Lowell. In the mid to late 1970’s, Armenian memory began to engage me. In certain distinctive ways, my poems began to engage Armenian culture and history—particularly the history related to the genocide and my grandmother’s survivor experience. These weren’t the only things that I was writing about, but they were beginning to percolate in my work.

N.B.—Ozone Journal, in some ways, reads like a memoir, giving insight into your inner world. What was this book able to accomplish that Black Dog of Fate did not?

P.B.—Poetry is not autobiography. It is fictional even though it comes out of personal experience. Memoir really has to toe the line with precise personal non-fictional experience; poetry does not. The poem is an imaginary invention. It’s very different than something like Black Dog of Fate.

N.B.—Ozone Journal seems very raw in some ways. There is some honesty in it…

P.B.—Honesty is essential and that’s an emotional and psychological orientation. I think it’s important that readers understand that poetry—while it comes out of personal emotion and perhaps some degrees of personal experience—is an invention. You’re inventing anything you need to invent to make the poem more truthful. Poetry is a foray into truth, a human experiential truth.

I write—and here I’m just playing with your idea of the word “raw”—in a very sharp, sensuous language that can be elliptical. I’m interested in capturing the tense nerve ends of syntax. Every line and phrase is a highly transformed act. It is a transformed and compressed piece of language. Every poem goes through 50 to 100 drafts. That’s what poets do; we’re obsessed with phrases and the nuances of linguistic music. If the reader thinks it flows, that means we succeeded [chuckles]. The intensity of compression and the decisions about where to cut, tweak, and move a phrase or an image are fundamental issues for a poet. Anyway, because you used the word “raw,” I wanted to note how much intense revising goes into making the “raw” [laughs]. I also hope readers realize poetry is about language and language is a modality of discovery, and the nuances of meaning are inseparable from the language density and inventions that a poet makes.

N.B.—When did you start writing Ozone Journal? How many years did it take for this to come together?

P.B.—I started Ozone Journal right after I finished Ziggurat, which came out in 2010. I probably started working on Ozone Journal in 2009 and finished it in 2014. Five years of work in this book.

N.B.— Discuss the time period reflected in “Ozone Journal,” the main poem.

P.B.—In the long poem, the persona is digging the bones of Armenian Genocide victims, with a TV journalism crew in the Syrian Desert in 2009. Yes, I was in the Syrian Desert with the 60-Minutes TV crew digging bones, but once you start inventing a poem, it becomes more than just an autobiography, even though some of this comes out of my own experience. Nevertheless, the character in the poem is looking back at his life in the complex and tumultuous decade of the 1980’s. Much of the poem is set in New York City in the 1980’s amidst the beginning of the character’s awareness of climate change, hence the title “Ozone,” the burgeoning AIDS pandemic of which a family member is dying, the breakup of a marriage, and single-parenting. This is not my personal narrative; it’s the character’s narrative. The conversations with the great jazz producer (based on George Avakian), who produced Miles Davis, take the persona or character into his explorations of sound and music, and time and space. All this is crisscrossing in a 55-section poem, which I call multi-sequencing.

N.B.—Talk about emptiness and absence, which seem to be central themes in the poem.

P.B.—Absence emerges out of the poem’s preoccupations with loss, as well as my preoccupations with loss—both in the historical sense, the ruins of culture. There is a strong sense of this [absence] in a poem about Gyumri and Ani, called “Near the Border.” Loss is part of this book’s grappling with the more sober meanings of life. Emptiness—in part—involves a search for higher consciousness and perhaps some degree of Buddhist-like detachment. I’m not a Buddhist, but I find it to be an important spiritual possibility. Those two [themes]—absence and emptiness—crisscross throughout various poems.

N.B.—You end that poem with the words: “If you feel the emptiness, you can see anything:/be in it: as matter, as matter of fact.” There is some sort of surrender and acceptance. Perhaps that’s what you’re calling the Buddhist detachment.

P.B.—There I am talking about higher consciousness rather than the losses from history; I am talking about trying to achieve that inner peace and tranquility or Buddhist emptiness. Yes, that’s true.

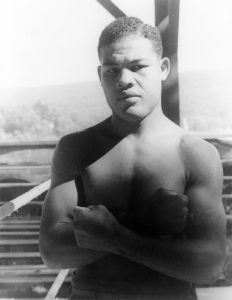

N.B.—In its own way, this book, which was published in the year of the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide, is a tribute to resilience and resistance. You mention human rights and civil rights activists, like James Meredith, in the book. There are symbols of resistance like the statue of Joe Louis’s Fist in Detroit. Talk about that.

P.B.—Images and figurations of the dispossessed appear in various poems. I have in my long poem a whole section about the Stonewall [riots*] and gay activists having their great moment of protest and breakthrough. The image of James Meredith in “Baseball Days ‘61” is a fleeting image in a young boy’s mind.

My poem “Slum Drummers, Nairobi,” is about the African musicians in Nairobi—who are known as The Slum Drummers. Here among other things I’m interested in the extraordinary resilience of the human spirit and imagination and its ability to create art out of adverse circumstances, and overcoming great odds and breaking through in creative ways against forces of power. “Joe Louis’s Fist” is about a number of things, but at the end of the poem, the power of the statue of Louis’s fist does embody an emblem of African American struggle and resistance against the system that has brutalized it. It’s all done through metaphor, image, and the historical representation of Joe Louis as a figure. That poem starts with Louis’s great fight of 1937 against the German Max Schmeling. It’s also a poem about Detroit, poverty, and so much more.

N.B.—There are also poems about [Taos] Pueblo—the Native American community. You mention the living conditions there.

P.B.—I’m interested in the richness of Native American culture. I realize I’m an observer; I’m a tourist looking on at this ancient civilization that has been disenfranchised by its conquerors. I’m looking on, observing a life of cultural richness and complexity. In the end, I’m more interested in complexity and paradox than I am in any kind of simple view of good and bad. I think the ethical issues will emerge more powerfully out of the complexity of language and perception than out of overt ideas.

N.B.—The multi-dimensional reality that you’ve created really comes through in the book. You create a space that’s very much pinned to a certain geography but also a little bit allusive. Help us understand this space in terms of globalization and identity.

P.B.—I see Ozone Journal as a transnational work. My imagination moves across borders and continents, from the slums of Nairobi to the Turkish Armenian border, to the Syrian Desert, to the Native American southwest, to the urban ruin of a great American city like Detroit. There is a lot of connectives between all these places in my work. I hope readers find that the poems rub up against each other and expand across global terrains. There’s a poem at the very end called “Home,” which really is my personal Armenian Diasporan vision.

N.B.—So where do you belong? Where is home?

P.B.—That poem. I want to throw my answer back, and just say to the reader, read “Home,” and tell me.

N.B.—What’s next for you?

P.B.—I’m working on a new book of poems that will be the third in this trilogy (Ozone Journal is the second). The plan is to also have a 50-section, multi-sequenced poem, which will complete a journey that was started in Ziggurat. I’m working on a prose book as well. I have nothing to say about it until it’s done [laughs], because I’m too superstitious. I’m working away.

* The Stonewall riots broke out in 1969, following a police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a bar popular with marginalized groups, including LGBT people, in New York City.