Ethnic communities urge Quebec to adopt mandatory genocide curriculum

- (0)

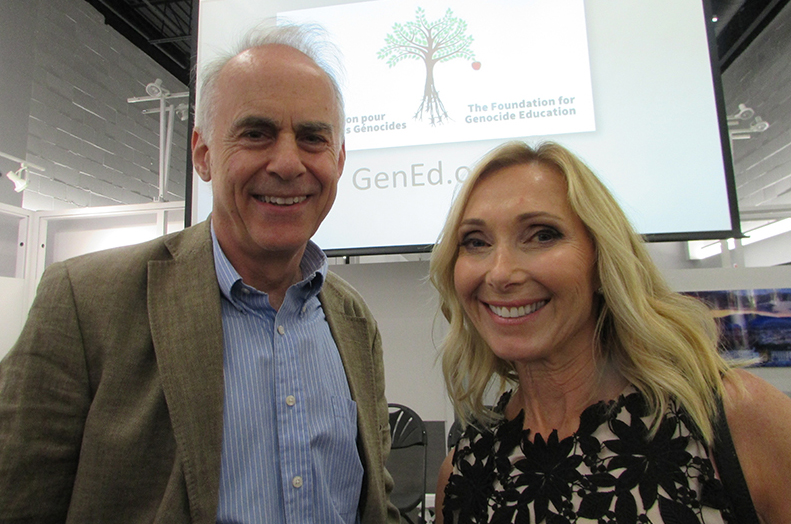

Heidi Berger, left, greets filmmaker John Curtin, the director of Why the Jews? (Janice Arnold/The CJN)

The Jewish, Armenian, Rwandan and other communities that have suffered mass atrocities have coalesced to urge the Quebec government to make the study of genocide compulsory in all high schools.

A campaign to raise $100,000 to develop curriculum materials for the proposed program was launched by The Foundation for the Compulsory Study of Genocide in Schools, a grassroots organization founded in 2014 by Heidi Berger to lobby for genocide education, on June 19.

Berger, the child of Holocaust survivors, believes that education is the key to preventing hatred and radicalization, and is dismayed that only passing reference is made to it in the province’s mandatory curriculum.

Last October, after years of being told by politicians and bureaucrats that it could not be done, the Education Ministry offered to partner with the foundation to form a working committee to develop resources for teaching about genocide.

That committee – composed of ministry staff, teachers, experts and foundation volunteers – has been meeting every since.

However, Berger said it is the foundation’s responsibility to fund those materials, including a teacher’s guide and an educational video that’s suitable for all schools. She is confident that these things will soon be available.

The June 19 campaign launch was hosted by the Kandy Gallery and attended by about 150 guests, including representatives of the Rwandan, Armenian, and Cambodian communities. Also present were representatives of the Muslim community, to which the foundation has reached out, as well as Education Ministry official Sarah Mainich.

No province has a mandatory genocide curriculum, Berger noted. The foundation’s ultimate goal is to see that the subject is taught across Canada.

The foundation is a registered charitable organization that’s administered through the Jewish Community Foundation of Montreal and relies solely on the private sector for funding. It grew out of Berger’s personal mission to talk about the Holocaust in schools around the province, following the death in 2006 of her mother, Anna Kazimirski, a survivor from Poland who for many years spoke to young people as a Montreal Holocaust Museum volunteer.

Berger came to realize that many teens do not know much about the Holocaust and other modern genocides. Many people don’t even know what the word “genocide” means, she said. “Survivors’ testimonies are not enough,” said Berger, “young people have to understand the steps that lead to genocide.

Most teachers are reluctant to do that. “They are either afraid, are not interested or say they don’t have time,” she said.

Until last fall, education ministers and civil servants were dismissive of what the foundation was trying to do. Berger attributes the breakthrough to Education Minister Sébastien Proulx.

“There are only two short paragraphs in the Secondary V history course on Terrorism and Conflict,” she noted. “The Holocaust is only referred to as a movement to deprive Jews of civil rights.”

The foundation also speaks about the mass killings in Bosnia and Darfur, as well as those in Syria, Iraq and Myanmar.

Mheir Karakchian, who’s Armenian, praised what the foundation has accomplished: “Three years ago, we had nothing. But we put our forces together and now we are a community, there is solidarity of the victims.”

Moses Gashirabake, a Tutsi survivor of the 1994 Rwandan massacre, also welcomed the initiative, saying that, “It’s not easy because Rwandan survivors do not like to speak out, but now, with the Jewish and Armenian communities, we can hold hands and support each other.”

Holocaust survivors Sidney Zoltak and Marguerite Quddus also endorsed the foundation’s work.

However, another audience member, Roman Serbyn, a retired history professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal, wondered why the foundation has made no mention of the genocide that took place in his native Ukraine, referring to the Soviet Union’s forced famine in the early 1930s.

Foundation spokesperson Marcy Bruck told The CJN that it will be included in the curriculum that’s currently being developed.

The documentary Why the Jews? by Montreal filmmaker John Curtin was also screened at the event. In it, lawyer Alan Dershowitz, Israeli President Shimon Peres, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks of Great Britain and Rabbi Reuben Poupko of Montreal, among others, offer opinions on how such a tiny and often persecuted group could have achieved so much.

Curtin’s father, who left Vienna in 1939, was Jewish, but the filmmaker was raised as a Catholic. The idea for the film began to germinate when he was a CBC reporter in Berlin and was surprised by the admiration Germans had for the Jewish people.

In the panel discussion, Rabbi Poupko said Jews are mistaken in thinking that anti-Semitism is rooted in jealousy. Anti-Semites dismiss those achievements because they see them as evidence of a Jewish conspiracy or influence, he said.

“Anti-Semitism is not despite, or in ignorance of, the accomplishments of Jews; it is because of those accomplishments. They remind anti-Semites of their failures, therefore they have to destroy those people.”

Canadian Jewish News