Canadians hurt by genocide share their stories for the good of humanity

- (0)

By Megan DeLaire

Nepean Barrhaven News

In the name of humanity, inclusion and acceptance, four Canadians affected by genocide gathered under one roof on March 20 to share their experiences with an audience.

Mirza Ismael was born to a Yazidi family in Iraq. He was forced to flee the ongoing persecution of Yazidi people – a non-Muslim ethno-religious group – but went on to found and chair the Yazidi Human Rights Organization International in Canada.

Vera Gara, born an Austrian Jew, survived life as a child in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Nazi Germany during the Holocaust. Since 1970 she has toured schools and conferences, sharing her story of survival and promoting inclusiveness.

Cevag Belian is a descendant of survivors of the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian genocide, carried out during the First World War. He directs the Armenian National Committee of Canada.

Denyse Umutoni was 24 years old and living in a village of 3,000 Tutsi people in Rwanda during the Rwandan genocide of 1994. When the genocide ended, she, her sister and five other people were the only survivors left in their village.

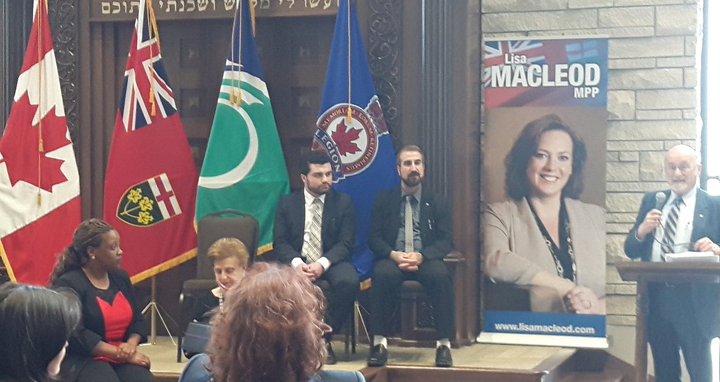

Together they formed a panel of survivors and representatives of survivors, one of several features of the Day of Humanity, Inclusion and Acceptance hosted by MPP Lisa MacLeod at the Ottawa Torah Centre in Barrhaven.

“In all of these instances, what we have is true positivity,” said Rabbi Reuven Bulka, who moderated the panel discussion. “People who lived in the ultimate negativity of murder, brutality, genocide, and escaped from it to do great things.”

Although their stories are different, they share a common motive for telling them: to promote inclusion through education and advocacy and, maybe, prevent future genocides.

In 1970, 15 years after she was liberated by Soviet forces in Germany, Gara moved to Canada – specifically Ottawa – with her husband and two daughters. The family was met with acceptance, and it’s acceptance that she encourages Canadians to demonstrate today.

“Nobody ever charged me of being a refugee or a foreigner,” she said. “Let’s keep on doing that and tell our children that no matter what, we are one … We have to remember that. We are all the same people, good and bad among all of us.”

Belian, the voice of a different generation affected by genocide, echoed the importance of keeping stories of genocide and inclusion alive long after they’ve taken place.

“I’m a descendant of survivors and victims … but their legacy and the stories that they’ve left behind is of course trans-generational,” he said. “The horrors of genocide and persecutions such as genocide transcend time and space.”

Anyone, the panellists agreed, can use that transcendence, to prevent future atrocities, whether or not they have been directly affected by genocide.

“April is the month to remember the (Rwandan) genocide, so invite your friends to come to listen to survivors,” Umutoni said. “Start where you are and it’s going to be OK … Pay attention to what’s happening. Look, judge and do better.”

Other highlights of the conference were the Tour for Humanity – a mobile human rights education centre – a lecture about Canada’s changing population demographics and presentations by local religious leaders and representatives including Jewish Rabbi Menachem Blum, Muslim Imam Zijad Delic and Aisha Sherazi, a spiritual counsellor for students and teachers at Merivale High School.

“One of the reasons why I love this conference is because there’s no negative words in it,” said Bulka.

“We’re not talking about anti-Semitism, we’re not talking about anti-this or anti-that. This is all positivity, humanity, inclusion, acceptance.”