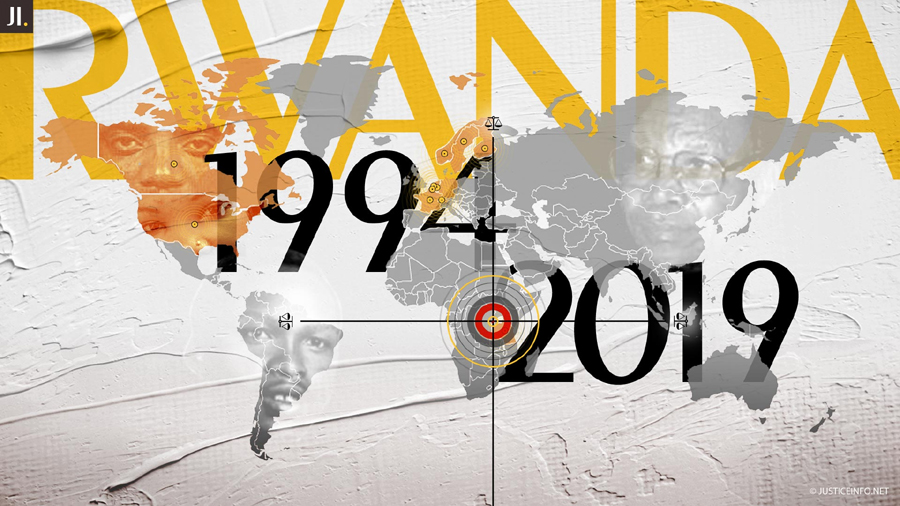

The parallels between the Rwandan and the Armenian Genocides

On December 8, the the Armenian National Committee of Quebec (ANCQ) was invited to be part of an event in Montreal organized by the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, PAGE Rwanda, and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights, which commemorated the 25th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide.

Humanities professor Dr. Lalai Manjikian was part of a panel representing the ANCQ. Below is her speech.

Distinguished guests, dear friends,

On behalf of the Armenian National Committee of Quebec, I would like to express our solidarity with the Rwandan community, as we mark the 25th anniversary of the Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

We stand in solidarity with the victims of the genocide and with those who survived.

Over one hundred years have passed since the Armenian genocide. Yet, we, as Armenians living in Canada, cannot remain indifferent to the Rwandan Genocide. Instead, Armenian-Canadians share your pain and stand united with you on this 25th commemoration so that two messages remain paramount in our common struggle against Genocide: First: Never Forget. Second, never stop working to prevent another Genocide.

The parallels between the Rwandan and the Armenian Genocides are chilling. The methodical planning and execution of the Rwandan Genocide on behalf of the Hutu mirrors the orchestrated annihilation of the Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire carried out by the Turkish Government headed by the Committee of Union and Progress (a.k.a the “Young Turks”) before and during the First World War.

In both cases, minority Armenians and minority Tutsis were demonized by state-sanctioned hate and racism. And in both cases, what makes these genocides so unspeakable is that they were preventable. The world knew, but did not act.

Furthermore, both Armenian and Rwandan Genocide survivors and their descendants live with the open wound of denial, which continues to be a direct assault on memory and truth. It has been said that the final stage of Genocide is denial. Similar to Turkey’s campaign to deny the Armenian Genocide, many known for their key roles in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide denied responsibility for the crimes they committed. Such denial only perpetuates the cycle of Genocides- making the world a more dangerous place and future genocides more likely.

Nothing makes Genocide more real than looking into the eyes of someone who has survived the unthinkable. I am always at a loss for words when I meet genocide survivors. What can I possibly say to them given what they have gone through?

So to address our panel’s main question, where do I turn for hope?

I find hope in a number of places.

For one, I find hope in the critical work conducted in various courts to bring the perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide against the Tutsi to justice. Holding those who planned, ordered, and carried out these horrific crimes accountable is absolutely primordial.

Secondly, I have been fortunate to follow, witness, and partake in the crucial grassroots work conducted by the Armenian National Committee across Canada and within the province of Quebec. The Armenian National Committee has been instrumental in ensuring that both the Quebec and Canadian governments officially recognized the Armenian Genocide back in 2003 and 2004 respectively.

Today, the Armenian National Committee continues to be committed to end the cycle of genocide through advocacy, through spreading awareness and especially through countering denialist discourses.

Thirdly, today I find hope in important initiatives such as the Foundation for Genocide Education, which was founded by Heidi Berger. The foundation aims to prevent the reoccurrence of genocide, namely through education. As a member of the board of the Foundation for Genocide Education, my colleagues and I are working with the Quebec Education Ministry, which is developing a guide on genocide education. This guide will be used by high school teachers in various disciplines. The Rwandan case is one of the genocides included in that guide.

Besides these formal initiatives that I mentioned, which aim to seek justice, spread awareness, and to stop genocide through education, I also find hope in more informal aspects of everyday life. I find instances of solidarity and bridge-building between communities that have suffered and survived through genocide to inspire empathy, healing, and good faith.

Allow me to share one particular instance that comes to my mind.

A few years ago, I was volunteering at an immigrant welcome centre here in Montreal.

As a volunteer, I was often assigned tasks by the receptionist, named Marie, a distinguished middle-aged woman.

One day, as I was pulling out immigrant files from a cabinet behind her desk, I finally asked where she was from originally, a very common question at the immigrant center. She answered “Rwanda” with precise pronunciation. Perhaps most conversations would have ended there, but I couldn’t help wanting to know more. As she recounted fragments of her tumultuous life, time slowed down a bit. The life events that had marked her journey were unimaginable.

All of a sudden, genocide became living history in that moment, in that immigrant centre, beyond anything written in books.

During our conversation, she was quick to acknowledge that Armenians had suffered a similar fate in the past.

She told me how her husband is still reeling from the atrocities and that he refuses to talk about those events.

I immediately recalled my grandfather who had survived the Armenian genocide and his reluctance to talk about the genocide unless stubbornly probed by one of us.

My volunteer shift at the immigrant centre was coming to an end for the day. I wish I could have offered Marie some sort of comforting closure to our conversation as a descendent myself, two generations removed from genocide, especially after she immediately opened up to me about her experience of persecution and escape.

Instead, I was simply mesmerized by the peace she carried, and her religious faith and unassuming inner strength.

I gathered my raincoat and purse, approached Marie and told her I wanted to give her a hug.

We were locked in each other’s arms for a few seconds.

Besides the historical importance that genocide survivor accounts possess, we have so much to learn from them about life, resilience, and determination.

We recognized each other’s pain, each other’s stories of loss, spoke of families being destroyed and how surviving members are dispersed around the world. My colleague and I had just built a bridge—continents, histories, and years apart—that we both knew, on an unspoken level, no one could ever break.

Lalai Manjikian, PhD