Iran calls for a “Wake-Up Call” to Moscow in South Caucasus

By Yeghia Tashjian

The post-November 10, 2020 geopolitical reality in the South Caucasus and the shift of balance of power have created not just an unfavorable situation for Armenia, but for Iran as well, which felt isolated from the region. Despite Tehran’s pro-active engagement towards the region, Iranian experts and politicians felt their legitimate concerns were being unheard in Moscow.

Many even publicly criticized the Russian leadership for working against Iranian interests in the region by cooperating closely with Turkey. This article will highlight some of the Iranian concerns directed at Moscow regarding the recent developments in the South Caucasus.

On what issues have Russia and Iran diverged in the region?

Iranian expert on the South Caucasus Vali Kaleji, in his article “Russia and Iran Diverge in the South Caucasus,” argued that despite the similarities in Iran’s and Russia’s approaches towards the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the South Caucasus, after November 10, 2020, the countries have diverged when it comes to the “Zangezur Corridor,” its impact on the Armenian-Iranian border and Israel’s relations with Azerbaijan. Moreover, after the war in Ukraine, Russia distanced itself from the developments in the region leaving Armenia alone in resisting the Turkish-Azerbaijani-Israeli axis. This factor has created a security and strategic dilemma for Iran along its entire northwestern border.

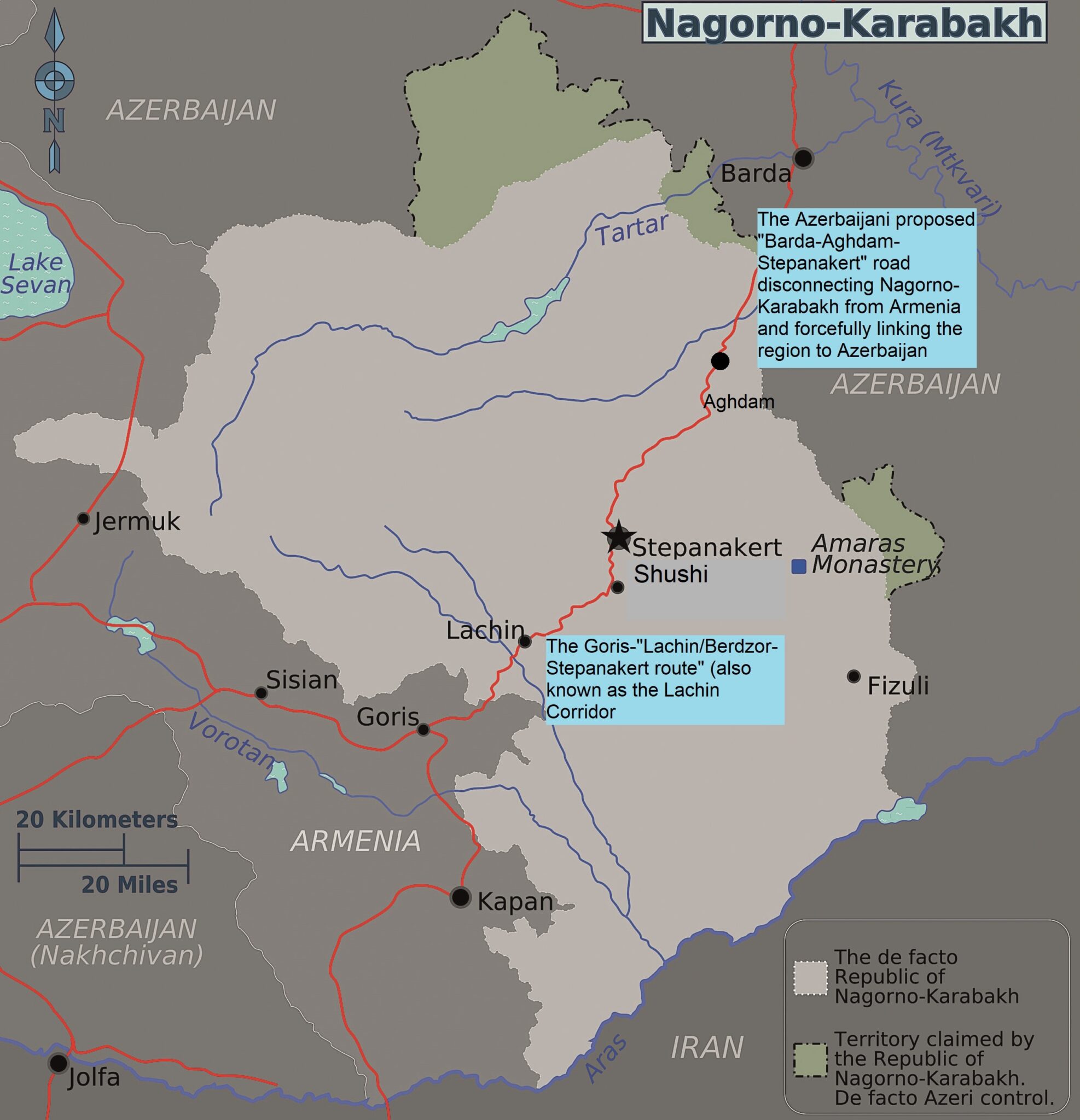

According to Kaleji, Iran had reservations about the fifth paragraph of the trilateral statement, which called for the establishment of the peacekeeping forces but also for establishing a Russian-Turkish joint monitoring center in Aghdam. (Iran did not participate in this mission.) In fact, while Turkey was not mentioned in the agreement, both Ankara and Moscow signed an MoU to establish the joint Russian-Turkish center to monitor the ceasefire in Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh). Interestingly, Iran, which was directly impacted by this war, was left out of the agreement, and according to the Iranian expert, this showed “Russia’s preparedness to disregard Iranian interests” in the region.

Another issue is the establishment of the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” project, to which Baku wants to have an uninterrupted and extraterritorial connection between Azerbaijan proper and the Nakhichevan exclave. When Russia’s ambassador to Baku Mikhail Bocharnikov said that the project has all the bases for implementation and he doesn’t see any “unsolvable differences on this issue,” alarms went off in Iran. Although many Russian high-ranking officials disregarded the term “corridor” (Russia’s FM spokesperson used the term “route”), Iran and Armenia are still suspicious of Russia’s main objective in controlling these routes and giving them a certain status. Iran’s concerns arise from the fact that Azerbaijan wants to cut the Armenian-Iranian border and isolate Iran. President Aliyev has occasionally threatened that if Armenia doesn’t give Baku a “corridor,” then Azerbaijan will take the land by force.

Third, Russia’s passive view of Israel’s role in the region has also raised some concerns in Tehran. Kaleji argues that while Iran is extremely worried about Israeli military and intelligence involvement in the region, as well as the threat of Israeli drones targeting Iranian nuclear centers and assassinating scientists, Moscow has been looking the other way. Moreover, “Russia has adopted an approach to Israel’s presence in the South Caucasus that is similar to that in Syria, which is definitely not favorable to Tehran,” argues the Iranian expert.

Iranians are aware that Russia’s war with Ukraine has shifted Moscow’s attention from the South Caucasus, while at the same time improving Russia’s economic relations and increasing trade via Turkey and Azerbaijan (the latter within the context of the International North-South Transport Corridor). As a result of this political vacuum, the Israeli-Turkish-Azerbaijani axis is being consolidated in the region, making Iran “extremely worried about geopolitical changes, the balance of power and changing international borders in the region,” argues Kaleji. Furthermore, the involvement of Russia in Ukraine also weakened the idea of the “3+3” format which Iran was pushing as a regional cooperation example to exclude the West and stabilize the region.

Kaleji also mentions that over the past three years, Russia has ignored Iran’s geopolitical concerns in the region. When tensions between Baku and Tehran ran high in September and October of 2021, Iran sought to cooperate with Russia to calm the situation. However, surprisingly, in a meeting between Iran’s and Russia’s foreign ministers, Sergei Lavrov expressed Russia’s opposition to Tehran’s military exercises along the Azerbaijani border. According to Iranian experts, the Russians were concerned that Iran’s military exercises and its involvement in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict would further complicate the situation in the region.

Another Iranian Expert Rings Alarm Bells for Russia

Dr. Ehsan Movahedian, a professor of international relations at Tehran’s ATU University, in an interview with the Armenian Weekly, argued that Russia intends not to allow Iran to act in the Caucasus and Central Asia and prefers to interact only with Turkey in these regions. The reason is that after the Ukraine war, Russia needs Turkey to bypass Western sanctions, sell energy and freely access the Mediterranean Sea. According to Movahedian, Russia’s behavior has caused Iran’s interests to be endangered, especially in the Caucasus, whereas NATO and Israel have penetrated this region and created security, political and cultural challenges for Russia, and especially for Iran.

The Iranian scholar argues that Russia has made a calculation error and does not pay attention to the fact that the situation in the South Caucasus has been complicated for a long time due to Russia’s conflict in Ukraine and Western interference in the Caucasus. Taking advantage of the power vacuum, Turkey is addressing the needs of NATO and Israel in the South Caucasus. Therefore, focusing on Russia in the South Caucasus and depriving Iran of its presence in this region will ultimately reduce Russia’s position and influence.

Movahedian also brings up the issue of the ongoing blockade on the Berdzor (Lachin) Corridor. It is important to mention here that the blockade over the Berdzor Corridor was anticipated. Azerbaijanis are now building a railway connecting Barda to Aghdam and plan to eventually extend it to the capital of Artsakh, Stepanakert. It is within this context that they are blocking the Berdzor Corridor. Previously, Azerbaijanis have asked the Russian side to use the Aghdam-Stepanakert route to supply their base in Artsakh, but the Russians have refused. Now, Baku is negotiating with the International Red Cross to send aid to Artsakh via Baku (Aghdam road) instead of Yerevan (Berdzor Corridor).

Baku successfully pushed the “Aghdam road” narrative during the recent summit in Brussels that was held between the President of the European Council Charles Michel, President Aliyev and Prime Minister Pashinyan. The European leader said, “I emphasized the need to open the Lachin road. I also noted Azerbaijan’s willingness to provide humanitarian supplies via Aghdam. I see both options as important and encourage humanitarian deliveries from both sides to ensure the needs of the population are met.” Thus, he undermined the importance of Berdzor and offered an alternate route. Azerbaijan wants to keep the Armenians of Artsakh captive, humiliate them and later push them out of their homeland. Movahedian perceives this as a sign of Russia’s weakness and wonders how Moscow, which has been unable to unblock the Berdzor Corridor, will be able to guarantee the safety of the trade routes in the region (specifically in Syunik as mentioned in the trilateral statement). Hence, “with this path, it will be Turkey and NATO that will be taking over the routes and isolating Russia and Iran from the region,” adds the Iranian scholar.

Movahedian concludes that Iran must hope that Russia’s repeated failures in interaction with Armenia and Azerbaijan and the reduction of Russia’s soft power and position in the Caucasus region will force the Russian leaders to reconsider their policy and allow Iran to expand its economic, security and political activities, especially in the south of Armenia, and find a way to “prevent the execution of the evil intentions of NATO, Turkey and Israel.” He also called on Russia to repeat in the South Caucasus the experience of joint cooperation with Iran in Syria, train the Armenian soldiers, and abandon its false and dangerous pride.

If not, the scholar warns that Iran may challenge Russia by creating obstacles for Russia’s access to the Persian Gulf. Some Iranian experts also argue that Iran should review the amount and quality of its military assistance and cooperation with Russia in connection with the war in Ukraine so that Russia reconsiders its “anti-Iranian behavior” in the South Caucasus.

Iran’s Former Foreign Minister Warns Moscow

On July 12, 2023, Ali Akbar Velayati, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Iran, published an article in Tasnim News Agency warning Moscow about its ineffective foreign policy in the South Caucasus.

In his article, Vilayati asks whether the true intention of Azerbaijan and Turkey was to have a transit route via Armenia to facilitate trade, gas and electricity exchange or to violate the sovereignty of Armenia. He mentions that now it is clear that the true intention is “first to divide Armenia into two parts and, second, to disconnect Iran and Armenia, severing a link that dates back to the era of the Achaemenid and Parthian Empires, and finally to limit Iran’s connection to the outside world and its connection with the North Caucasus, Russia and the European continent.”

The former Iranian FM argued, “Our strong guess is that the issue of establishment of a connection between Istanbul and Xinxiang, more than signifying the formation of an imaginary world named pan-Turkism, given the scope of Turkey’s ties with NATO, will lead to the creation of a strip that will surround Iran from the north and Russia from the south and spread NATO’s influence in the region. The opening of the Nakhichevan path, instead of developing trade and cooperation, may cause NATO and some of its members that play a role in this conflict to pave the way for the more serious and active presence in all facilities and access points in the north of Iran and south of Russia.” Vilayati concluded his remarks by criticizing the Western interference in the region and calling upon the Russians to be “careful and know that any negligence in the Caucasus will make it a place for invasion and rivalry among different countries and ill-intending parties that would attack the interests of Russia and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” hence undermining the security of the entire region.

Conclusion and Reflection

The aforementioned factors have pushed Iranian experts and politicians to raise concerns and warn Moscow about the situation in the South Caucasus. Many Iranian experts believe that Iran alone cannot contain the Israeli and Turkish infiltration and needs Russia’s cooperation. This situation has left Iran in a defensive (rather than aggressive) position on the issues of maintaining the territorial status quo along the Armenian-Iranian border and confronting Israel’s security and intelligence presence along Iran’s northwestern borders.

In the last few months, dozens of articles have been published in the Iranian media raising concerns about the humanitarian situation in Artsakh, the blocking of the Berdzor Corridor, and the Israeli presence in the territories captured during the 2020 war. Some of these articles even touched on Aliyev’s threats on occupying Syunik and establishing “Western Zangezur” and “returning” Azerbaijani “refugees” to this region. Iran understands very well that the establishment of the “corridor” is the first step to annexing southern Armenia and encircling Iran from the north.

Both Tehran and Moscow, to secure their national interests in the region and prevent a “great catastrophe” in Artsakh which will ultimately have a spill-over effect in the bordering regions of Armenia, have to coordinate with Yerevan, irrespective of their mistrust of the current Armenian authorities. If the Turkish-Azerbaijani-Israeli project succeeds in Artsakh, it will be too late for already exhausted Moscow and encircled Tehran to reverse the balance of power, as Yerevan will directly accuse Moscow of abandoning its obligations and may move towards the West. This will put both Moscow and Tehran in a politically difficult position. To prevent the occurrence of this catastrophe, Moscow, to save its image in the region, has to prioritize the unblocking of the Berdzor Corridor and guarantee the physical security of Armenians in the unrecognized republic and must take Iran’s concerns more seriously.

Comments are closed.