What the Nazis saw, and didn’t see, in Kemal Ataturk

- (0)

What the Nazis saw, and didn’t see, in Kemal Ataturk –

Thomas A. Kohut

The Weekly Standard

However, a young German scholar, Stefan Ihrig, educated in Britain, has done just that. He has discovered the important role played by Kemal Atatürk and Atatürk’s Turkey in the Nazi imagination. Ihrig’s book, which focuses first on the early 1920s and then on the Third Reich, is based on his reading of the public statements and written expressions of leading Nazis relating to Turkey, and even more on his exhaustive examination “of thousands of articles from German newspapers from the early 1920s and the Third Reich.”

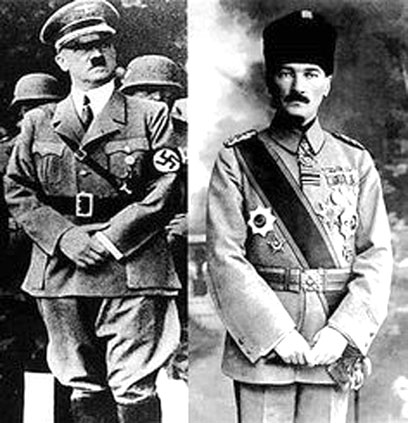

Ihrig argues that the Nazis, including Adolf Hitler, saw and presented Turkey under the leadership of Kemal Atatürk as an inspiration and a model for the new Reich they sought to create in Germany—first, during the early years of the Weimar Republic, and then during the Third Reich itself. Despite the fact that Turkey was initially neutral and ultimately joined the war against Germany on the side of the Allies in World War II, Nazi leadership and the Nazi press remained sympathetic to Atatürk and Atatürk’s Turkey until the Third Reich’s bitter end.

The Ottoman Empire had long been an object of “orientalist” fascination for Germans. Despite its apparent exoticism, however, the empire was regarded as Germany’s natural ally, particularly during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The relationship culminated in Turkey’s alliance with Germany in the First World War.

Nevertheless, it was the Turkish war of independence, which began in May 1919 and ended in mid-1923, that made Turkey and Mustafa Kemal heroic exemplars for Germans. The war established the boundaries of modern Turkey and, most significantly for the Germans, resulted in the revision (in the Treaty of Lausanne) of the “Turkish Versailles,” the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, which had dismembered the Ottoman Empire, leaving Turkey something of a rump state. Turkey’s revision of a humiliating treaty, and the attendant nationalist revival in Turkey under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, became (in Ihrig’s words) a “major Weimar media event” during the early years of the shamed, “desperate and desolate” republic.

A resurrected and revitalized Turkey was held up as a “role model” for Germany, and Kemal was celebrated as a nationalist hero, particularly in newspapers on the far right of the political spectrum. Rather than being seen as exotic or oriental, Turkey was now portrayed as “similar, and comparable to Germany” in the nationalist press. If Turkey could achieve the revision of a humiliating peace treaty and produce an authoritarian, inspiring leader to resurrect the nation, then Germany could as well.

There were a number of right-wing enemies of the Weimar Republic who saw themselves as potential “German Mustafas”—Adolf Hitler not least among them. Based on his reading of the Nazi press in the period before November 9, 1923, Ihrig boldly claims that Hitler’s failed putsch attempt in Munich on that date “was inspired much more by Mustafa Kemal and the events in Anatolia than by the example of Mussolini’s ‘March on Rome.’ ” Indeed, according to Ihrig, Atatürk’s critical influence on Hitler’s thought and action has generally been overlooked in historical literature in favor of that of Mussolini.

Ihrig contends that “Mustafa Kemal Pasha must have been a key influence in the evolution of Hitler’s ideas about the modern Führer and about himself as a political leader” during the early 1920s. The fact that the Nazi press and Hitler spoke favorably about Atatürk and the Young Turk revolution does not necessarily mean that the actions of the Nazis and of the future Führer were inspired by them, or even that Atatürk was more important than Mussolini in the Nazi imagination. Nevertheless, Ihrig presents convincing evidence that Atatürk’s “Turkish example” was important to the Nazis and to Hitler in the first years of the Weimar Republic—that they hoped to achieve in Germany what they perceived to have been Atatürk’s accomplishments in Turkey, and even that there was “a Turkish, Kemalist dimension” to Hitler’s 1923 coup attempt.

Following the failed putsch, Turkey and Atatürk were mentioned relatively rarely in the press during the Weimar Republic, suggesting perhaps that their appeal related primarily to the revision of the victors’ peace that had been imposed on both Turkey and Germany at the end of World War I. Nevertheless, the Nazis and Hitler lost none of their admiration for Turkey or its leader in the years leading up to the Nazi seizure of power, and after early 1933 there were renewed public expressions of appreciation of Atatürk and his Turkey in the Nazi press.

Indeed, in an interview that year, Hitler described Mustafa Kemal as “the greatest man of the century” and the new Turkey as having been “a shining star” for him. During the Third Reich, Nazi propagandists portrayed the Turks as racially related to Aryans: They propagated a “cult of Atatürk,” which reached a climax with his death in 1938. The example provided by the “Turkish Führer” proved that history was not made democratically but through the actions of great men. And the example provided by Atatürk’s Turkish state demonstrated the superiority of one-party rule—indeed, of one-party rule in an ethnically and racially homogeneous völkisch nation.

Whereas backward Ottoman Turkey had been multiethnic and multi-racial, Atatürk’s modern Turkey was purportedly ethnically and racially homogeneous. The massacre of the Armenians was presented in the press as “one of the main foundations of this vibrant new völkisch state.” It, together with the subsequent expulsion of the Greeks following the Treaty of Lausanne, had “resolved” the Turkish “minority question.”

In its celebration of Turkey as a fellow völkisch state, the Nazi press conveniently overlooked the non-Turks—Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Kurds, and others—who continued to reside in Turkey. Atatürk was lauded for his secularism and for his efforts to restrict the influence of Islam, which, in the press’s view, had long retarded Turkish development—an attitude that reflected the Nazis’ own (oft-masked) aversion to Christianity, particularly Roman Catholicism. Finally, Atatürk’s Turkey was celebrated as a country under construction, well on its way to becoming a model modern nation-state, despite the fact that it remained largely agricultural and lagged significantly behind Western European countries in industrial development.

Here, as was often the case, the Nazi media and Nazi leadership frequently ignored or grossly distorted the reality of Mustafa Kemal and his nation. Thus, although Ihrig presents Atatürk and Turkey as having inspiredthe Nazis and Hitler—as much as or perhaps even more than Mussolini and fascist Italy had—I found his other claim, that Turkey served as a screen onto which the National Socialist media and leadership projectedNazism’s own agenda and celebrated Nazism’s own achievements, more convincing.

Ihrig does not much deal with the reality of Atatürk’s Turkey. Nevertheless, that reality appears, despite certain superficial similarities, to have diverged significantly from the version found in the Nazi imagination—not least the fact that Atatürk thought Hitler to be a “tin peddler” (probably “fraud”) and regarded Mein Kampf as the ravings of a madman. Atatürk was decidedly unsympathetic to National Socialism and generally sought to distance himself from Nazi Germany. Indeed, the idea that Atatürk and Turkey served less as an inspiration for Hitler and the Nazis and more as a projection screen helps to account not only for the Nazis’ ability to overlook features of Atatürk’s Turkey that did not conform to their fantasies, but also for the fact that their affection for Turkey was relatively unaffected by Turkey’s actual policies, its good relations with Bolshevik Russia, and its initial neutrality and ultimate military intervention on the side of the Allies in World War II.

Stefan Ihrig has written a valuable and important book. He has shed light on an overlooked, remarkable, and significant aspect of National Socialism: namely, the prominent role played by Turkey and Kemal Atatürk in the Nazi imagination. This is a notable accomplishment. Indeed, I look forward to his forthcoming Justifying Genocide: Germany, the Armenian Genocide, and the Long Road to Auschwitz.

Thomas A. Kohut, the Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III professor of history at Williams, is the author, most recently, of A German Generation: An Experiential History of the Twentieth Century.