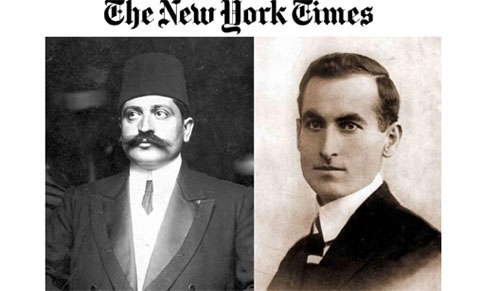

Talaat Pasha Slain in Berlin Suburb – The New York Times, March 13, 1921

Talaat Pasha Slain in Berlin Suburb – The New York Times, March 13, 1921

Armenian Student Shoots Former Turkish Grand Vizir, Held Responsible for Massacres

Morgenthau Tells of Talaat as “Big Boss” and Blames Him for Atrocities

Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

BERLIN, March 13, –Tallaat Pasha, former Grand Vizir of Turkey and one of the three leaders of the Young Turk movement, was assassinated here today.

He was walking in a street in a western suburb with his wife when a young man who had been following overtook them and, tapping Talaat on the shoulder, pretended to claim acquaintance with him. Then, drawing a revolver, the man shot Talaat through the head and with a second shot wounded the wife. Talaat fell to the pavement, killed instantly.

The deed was witnessed by many passersby, who seized the assassin, beat him and had almost lynched him when the police intervened. In broken German the murderer said to the police: “We are both foreigners. This has nothing to do with you.”

He was eventually identified as an Armenian student, and it is assumed that the deed was an act of revenge for the massacres of his compatriots.

Talaat, whose name was on the second Entente list of Turkey was criminals left Constantinople two years ago and had been living as a fugitive ever since under assumed names, first in Switzerland and later in Germany. He evidently feared the fate which has now overtaken him, for he had frequently changed his address in Berlin and at the time of his death was living at a pension in the West End.

BERLIN, March 15 (Associated Press). — The assassin of Talaat Pasha is said to be Solomon Tellirian.

Condemned for War Rule in Turkey

Talaat Pasha, with Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha, formed the triumvirate which controlled the Turkish Government during the war.

In July, 1919, a Turkish court-martial investigating the conduct of the Government during the war period, condemned the three to death. At the time the sentence was pronounced, however, Talaat had already fled to Germany, in which country Enver Pasha and Djemal also took refuge. Enver has since returned to Turkey and joined the Nationalists.

Responsibility for the massacres of Armenians was thrown on Talaat Pasha, and shortly after his arrival in Berlin it was reported that the Turkish Government would demand his extradition, along with that of other Turkish Generals. It was said that the Turkish Government intended to punish Talaat and the others for the Armenian atrocities, but #he never was extradited.

Talaat Pasha had held many portfolios in the ministers of Turkey including those of the Interior. Marine and war, and Posts and Telegraphs. In May 1919, Cecil Harmsworth, British Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, announced in the House of Commons, that the British Government would take steps to bring Talaat Pasha to account for his share of Turkey’s war guilt, but nothing was done in this regard.

An unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Talaat was made in Constantinople early in 1915, at which time he was seriously wounded by the would-be murderer’s bullet.

Morgenthau Blamed Him for Massacres

Henry Morgenthau, who dealt extensively with Talaat while he was Ambassador to Turkey and who probably knew him better than any other American, said last night that his investigations had left in his mind no doubt that Talaat was responsible for the Armenian massacres. He added that Talaat was a man of great cleverness, but absolutely ruthless.

In his book, “Ambassador Morgenthay’s Own Story,” Mr. Morgenthau refers repeatedly and vividly to Talaat, whom he describes as the “Big Boss,” of Turkey. The book describes in details how Germany through military and political penetration forced Turkey into the war and how Talaat and Enver, as tools of the German war machine, brought about numberless atrocities.

Describing his work of getting foreign residents out of the Ottoman Empire during the war, Mr. Morgenthau tells of Talaat’s promise to prove that the Turks were not barbarians by showing that they could treat foreigners decently, of how a train that was to take a number of aliens out of the country was held up repeatedly and then of a visit to Talaat to find out why his promise had not been kept.

Mr. Morgenthau contrasts the aristocratic, luxurious life of Enver with the unpretentious Talaat, whom he found living in a squalid, narrow street guarded by a policemen at each end.

“Talaat’s house,” Mr. Morgenthau writes, “was an old, rickety wooden three-story building. All this, I afterward learned, was part of the setting which Talaat staged for his career. Like many an American politician, he had found his position as a man of the people a valuable political asset, and he knew that a sudden display of prosperity and ostentation would weaken his influence with the Union and Progress Committee, most of whose members, like himself, had risen from the lower walks of life.”

Visit to Turkey’s “Big Boss”

Mr. Morgenthau describes the humble interior of the home, and continues:

“Amid these surroundings I waited for few minutes the entrance of the Big Boss of Turkey. In due time a door opened at the other end of the room and a huge, lumbering, gaily decorated figure entered. I was started by the contrast which this Talaat presented to the one who had become such a familiar figure to me at the Sublime Porte. It was no longer the Talaat of the European clothes and the thin veneer of European manners; the man whom I saw looked like a real Bulgarian gypsy.

“Talaat wore the usual red Turkish Fez, the rest of his bulky form was clothed in thick gray pajamas, and from this combination protruded a rotund smiling face. His mood was half genial, half deprecating; Talaat well understood what pressing business had led me to invade his domestic privacy, and his behavior now resembled that of the unrepentant bad boy in school. He came and sat down with a good-natured grin and began to make excuses.”

The account goes on the tell of Talaat’s unveiled, intelligent-looking wife punishing the Grand Vizier’s adopted child not the room with coffee and cigarettes, of the debate in which Talaat blamed the Germans and in which Mr. Morgenthau warned him that to yield was to place himself in the Teuton’s power and of how Talaat finally yielded to argument. It continues:

“Talaat turned around to his table and began working his telegraph instrument. I shall never forget the picture; this huge Turk sitting there in his gray pajamas and his red fez. Working industriously his own telegraph key, his young wife gazing at him through a little window and the late afternoon sun streaming into the room.

“We remained there more than two hours,” writes Mr. Morgenthau, “My involuntary host pausing now and then in his telegraphing to entertain me with the latest political gossip.”

In the end, he tells at the conclusion of the chapter, everything was arranged.